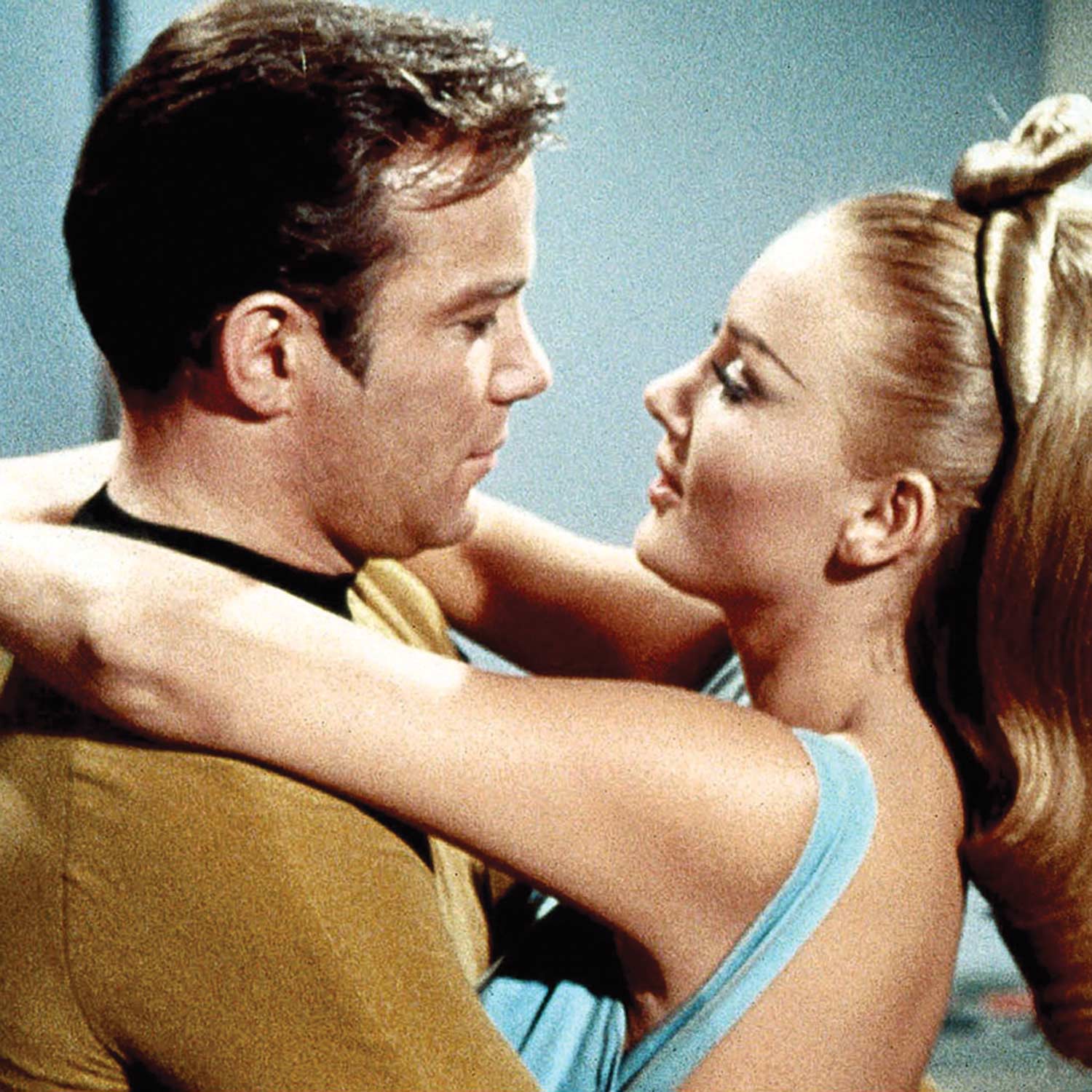

The show attracted a small but passionate following in its three-season run. That fan base would grow exponentially in size and influence in the 1970s, as a generation of latchkey kids tuned in to Star Trek reruns, a staple of after-school broadcast lineups. From that decade forward, Star Trek grew as a franchise.

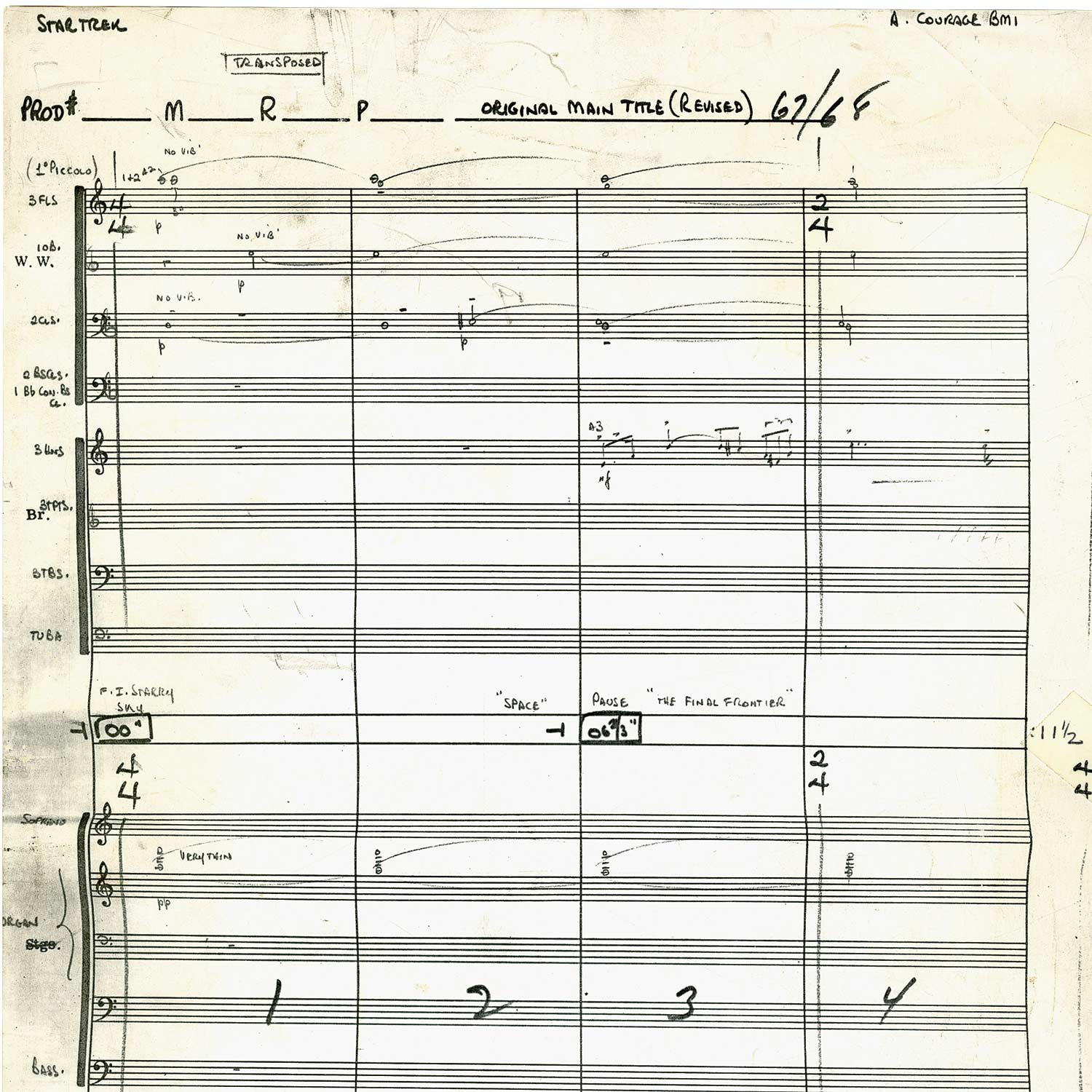

Rochester faculty and alumni have made important contributions to the show, starting with its iconic theme, the work of composer Alexander Courage ’41E.

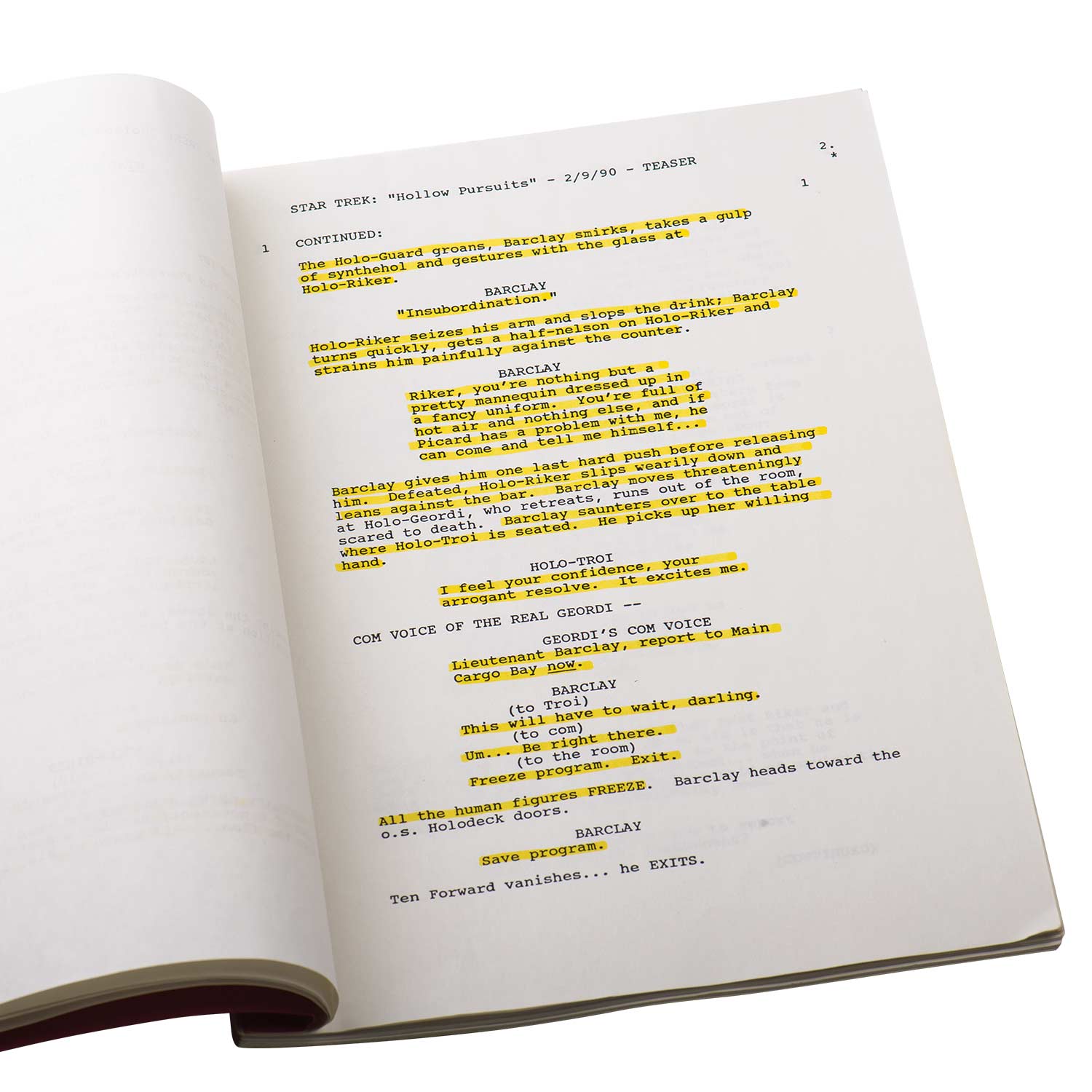

Reginald Barclay, the awkward, brilliant Next Generation lieutenant whom cohorts derisively nickname “Broccoli”—before he ends up saving the Enterprise—is the creation of Rochester English professor Sarah Higley.

From the beginning, Star Trek has attracted a cerebral sort. It had geek appeal long before geekdom became the badge of honor it is today. We shouldn’t be surprised, then, to find an abundance of steadfast fans among Rochester faculty and alumni.

By Karen McCally ’02 (PhD) with additional reporting bySofia Tokar and Dawn Wendt | Illustration by Steve Boerner (NASA models)

Alexander Courage ’41E

Composer

“I have to confess to the world,” said the late Alexander Courage ’41E in 2000, “that I am not a science fiction fan.”

Oh, the irony.

From its eerie first notes, to its arresting fanfare, to soaring climax, the theme that Courage composed for Star Trek in 1966 is among the most iconic in all of film or television.

Jeffrey Tucker

Associate Professor of English

“There was a kind of utopian vision that the show offered,” says Jeffrey Tucker, a science fiction expert who teaches a course on utopian literature.

“A key aspect of utopian philosophy is the notion of hope. Hope is a forward-looking psychological process, and just the notion that the status quo can be revised and improved— and even, I think my father said, that the species will survive and exist into the 22nd or 23rd century—in the mid-to-late 1960s that idea probably had a lot of weight. It was during the Cold War. It was the Vietnam era.” And the species does more than survive in Star Trek, Tucker adds.

Sarah Higley

Professor of English

Sarah Higley was in her third year of teaching medieval English literature at Rochester when she drafted a script for Star Trek: Next Generation. Having grown up on The Original Series, she started watching The Next Generation and quickly found herself both intrigued and skeptical.

Higley was fascinated by the holodeck, which had become a major feature of the Enterprise starting early in the first season. The holodeck was an enclosed room programmed to simulate any environment and create any holographic characters its users chose.

--->

--->

Thomas Perry ’74 (PhD)

Novelist and screenwriter

Thomas Perry and his wife, Jo Perry, are both trained as scholars of literature, and both turned to novel and screenwriting as their profession. They’d been writing steadily for the CBS prime-time television series Simon & Simon in 1990 when they cowrote “Reunion,” episode 80 of Star Trek: The Next Generation.

In the earliest days of email, as we collectively marveled at our newly expanded capacity for instantaneous communication, the staff of Academic Technology Services was inspired to name the University’s servers after Star Trek characters. Which email server were you on?

Aviva Dove-Viebahn ’10 (PhD)

Honors Faculty Fellow, Barrett, The Honors College at Arizona State University

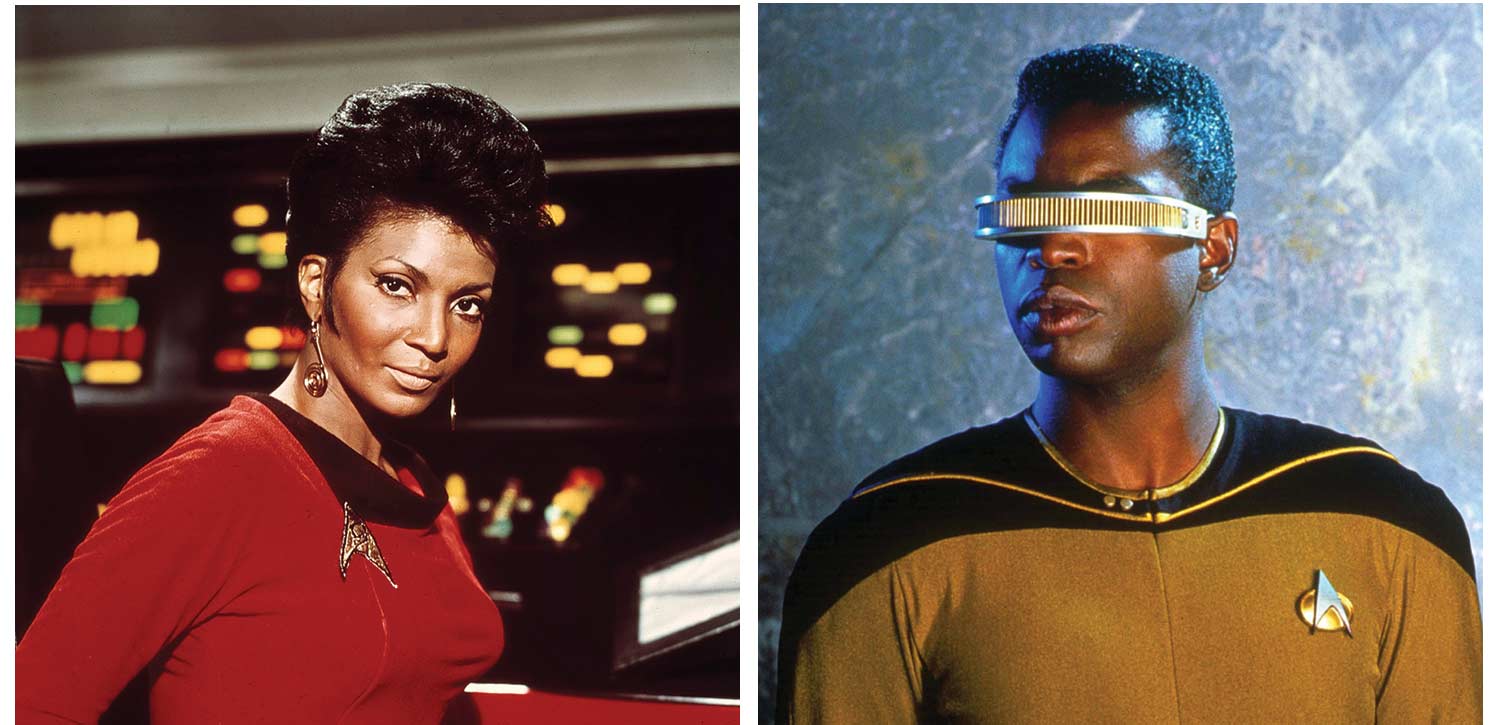

Science fiction has often been perceived as the province, primarily, of men—fantasy worlds chock full of gadgets and ultrapowerful humanoids. The irony, says Aviva Dove-Viebahn, is that science fiction “allows you to really play with social norms and to buck social norms”—including gender roles and stereotypes.

As a teenager, Dove-Viebahn was captivated by Voyager in large part because of the show’s female lead, Captain Janeway. Janeway “was a scientist and an explorer,” she says, “and fully invested in this role without being super girly, and without being masculine either.”

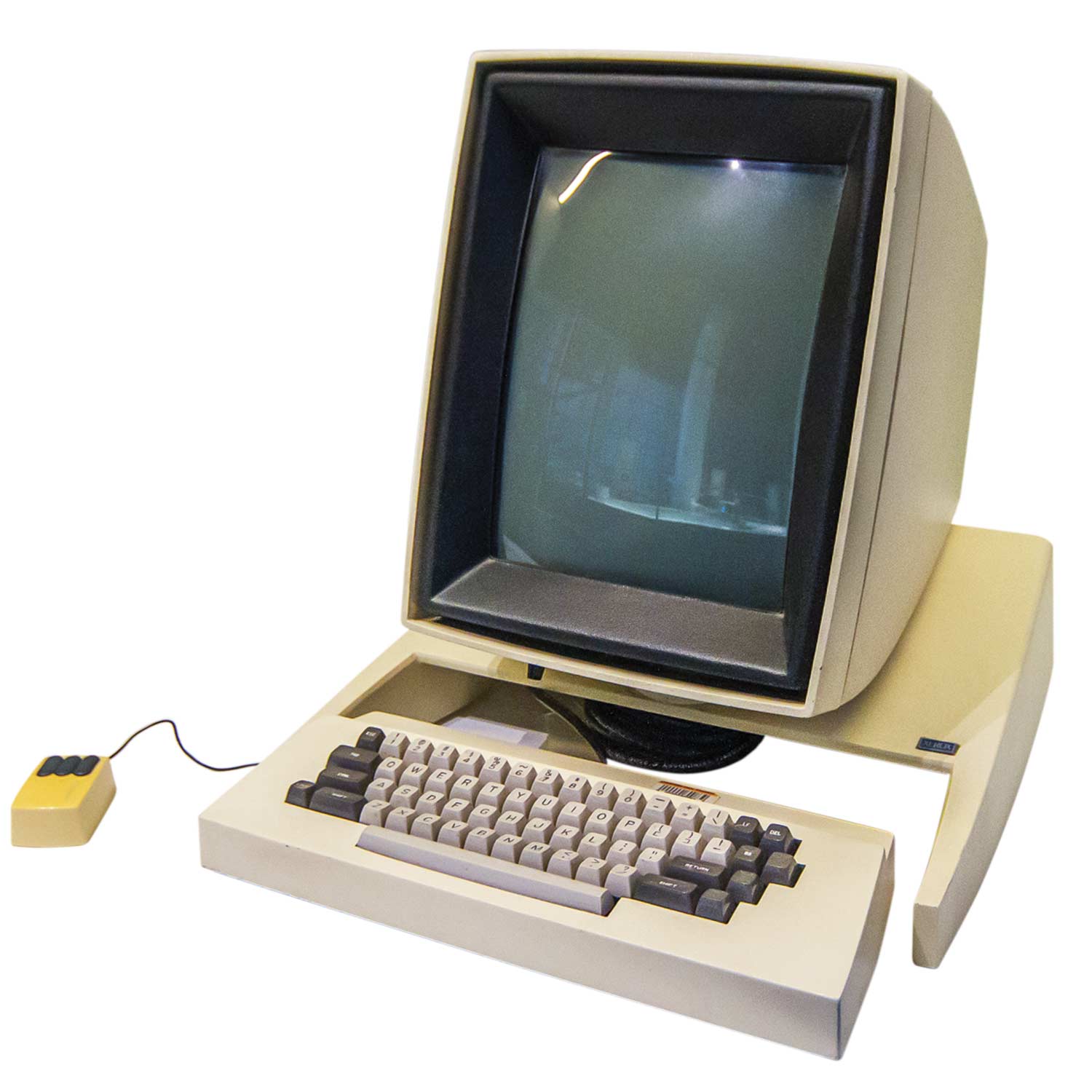

As graduate students in computer science at Rochester, Rick Rashid ’80 (PhD) and Gene Ball ’82 (PhD) codeveloped the Star Trek–inspired Alto Trek, one of the earliest networked computer games. Designed for play on the Xerox Alto computer, the game involved play in a universe of 16 star systems and included spaceships (named Klingon, Romulan, and Terran) and weaponry from the show.

Dan Watson

Professor of Physics and Astronomy

Among people in science and technology, Star Trek fans abound. Dan Watson, chair of the physics and astronomy department, is among them.

But that’s not because the series or films illuminate much about science. Watson shows Star Trek films to his introductory astronomy students to show what’s wrong with their depiction of physical science. “Astronomy 102 students learn enough about strong gravity, black holes, and time machines to detect the mistakes, and doing so is a good exercise for them,” he says.

William FitzPatrick

Gideon Webster Burbank Professor of Intellectual and Moral Philosophy

“From its very beginning,” says William FitzPatrick, Star Trek “explored themes of good and evil, power and moral corruption, peace and inescapable violence, and racism and equality; and in particular, took up issues concerning the moral standing of wildly diverse kinds of beings, from humanoids to intelligent energy clouds to sentient androids.”

Many episodes inspired deep reflection. But one of FitzPatrick’s favorites is “City on the Edge of Forever,” which originally aired in spring 1967, during the first season.