Features

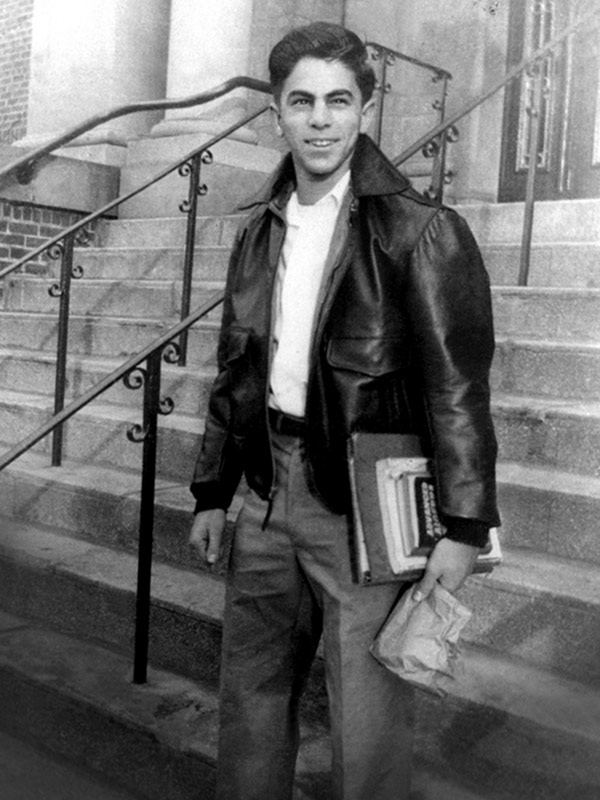

ROCHESTER BOUND: Hajim realized he was ready to “build a new future.” (Courtesy of Ed Hajim ’58)

ROCHESTER BOUND: Hajim realized he was ready to “build a new future.” (Courtesy of Ed Hajim ’58)From the Orphanage to the Boardroom

By the time he enrolled at Rochester, Ed Hajim ’58 had lived in more than 15 different places, from foster homes arranged by Catholic social service agencies in California to orphanages operated by Jewish organizations in New York City. As a toddler, the young Hajim had been taken by his father from his mother’s family in St. Louis and driven to southern California, where his father then placed him with foster families while he sought work on commercial and merchant marine ships. The pattern of parental neglect continued until Hajim set foot on the River Campus as a teenager.

That early sense of desertion and resilience fueled an unlikely success story, as Hajim worked to become a prominent Wall Street executive, financier, and philanthropist.

In a new memoir, On the Road Less Traveled, Hajim tells his life’s story for the first time, including his time on campus and his longtime connections to the University.

I arrived at the University of Rochester campus in the fall of 1954 alone with just a black leather jacket and an ROTC scholarship.

Let me explain. First, my clothes were cheap looking and way out of style. I stuck out like a sore thumb among my fellow students. My black leather jacket didn’t fit in with the more conservative clothes other people were wearing. And no one I saw on campus had my kind of haircut, so my appearance contributed to my feeling of self-consciousness.

In addition, inwardly, I chose to lock up my past and bury it for good. I vowed never to speak of my origins. I didn’t want my classmates to know where I came from or how hard I had to work to get there. If someone asked about my past, I didn’t answer. I felt so ashamed of it all—the orphanages, the poverty, the loss of my mother and abandonment by my father, the years of feeling so lonely and isolated. In my mind, keeping my past secret was the only way I could break free from it. It was as if I had to cut off the reality of my past to build a new future.

I think the new friends I met sensed my secrecy and sensitivity. Once they saw how I reacted to their inquiries, they quickly backed off and knew not to “go there” with me. There was one classmate from high school who also was attending Rochester, but I made it clear to him that I didn’t want my past discussed.

Because my father was part of that past, I placed all the letters Dad had written to me in boxes and stored them away. I told everyone he was a merchant marine and spent most of his time at sea. If I was asked, I’d say that my mom died in childbirth, because that’s what my father had told me. I made no further information available. The truth was, I was humiliated and embarrassed by my past—and that included my father, a man who despite his talents was never able to support me emotionally or financially.

Expending all this energy covering up gave me a dark side. I often felt a return of the rage I had experienced during my childhood. But as I look back on it now, I can see that this inner turmoil also drove me to succeed in ways I could never have imagined. Back in those days, going to therapy was uncommon, so I didn’t seek professional help in dealing with my feelings, even though I needed it. Instead, I just continued to keep myself as busy as possible, piling extracurricular activities on top of the very rigorous academic program I’d chosen for myself.

My Magic Two Words Are ‘What’s Next?’

Ed Hajim tried to hide the story of his life from most of the people who know him. Even his wife, Barbara, and their children, G.B., Corey, and Brad, didn’t get the entire account until 2008, when Hajim was named chair of the University’s Board of Trustees.

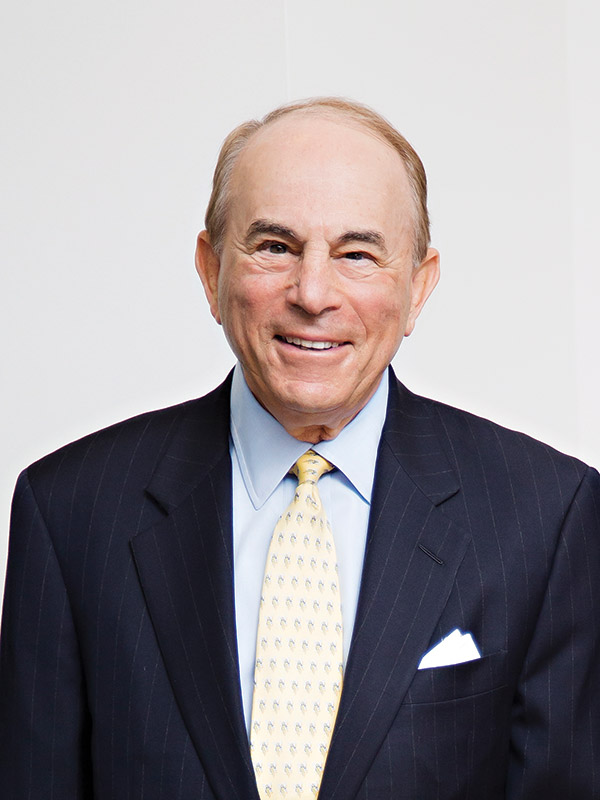

STORYTELLER: After being embarrassed by his early life, Hajim decided to tell his story because “it might help other people.” (Shannon Taggart for the University of Rochester)

STORYTELLER: After being embarrassed by his early life, Hajim decided to tell his story because “it might help other people.” (Shannon Taggart for the University of Rochester)Despite a five-decade connection to the University that began when he was a student, Hajim kept his background as a child who grew up in foster homes and orphanages as private as he could. Today, as a successful philanthropist, Hajim sees himself in a position to help students with hardscrabble backstories like his.

“In the end, adversity is a gift,” Hajim writes in his new memoir, On the Road Less Traveled (Skyhorse Publishing, 2021). “If you don’t experience it, you’ll never know how to overcome it. The disadvantages I endured sparked my ambition and work ethic. So it wasn’t fate. It was drive—some call it grit. It’s the one thing privileged people who feel entitled to everything and have nothing to fight for often lack. That was never me.”

His life’s story is harrowing but ultimately a story of success. As a toddler he was, for all intents and purposes, kidnapped by his father, led to believe that his mother was dead most of his life, and was left to fend for himself in foster services and orphanages. He worked to become one of the late 20th-century’s most successful Wall Street executives as well as a major philanthropist. A generous supporter of education, Hajim committed $30 million to Rochester, the largest single gift in the University’s history.

Working with his family, Hajim spent seven years on the memoir. In completing it, he realized that recounting his story might help other people.

“To me, if you could help a few people have it a little bit easier on their trip through the forest, then you’re doing something,” he says. “Love is doing things for other people. And this seems like the right time.”

Why did you want to write a memoir?

I was very embarrassed by my back history, so I buried it for most of my life. In fact, my wife, Barbara, really didn’t get the whole story for a long time. The kids got pieces of the story. Nobody got the story until I came to Rochester to become chairman of the Board of Trustees. I was planning to make the gift anonymously, but Jim Thompson [then chief advancement officer] said, “We can’t do that.” And Mark Zupan [then dean of the Simon Business School] started digging into my background—typical research guy—and found some details. I watched this, and I thought, “You know, you’re 72, we’ve got to get this down on paper.” Once I started writing it, I really wanted it to be private and self-publish it and give it away to friends. But you start to learn things when you start to write.

What did you learn?

Your background is very important to you. It can give you advantages and disadvantages. Even when you have a very disadvantaged background, it gives you certain definite advantages that other kids don’t have. Think about me, going 15 different places before I was 18 years old. Am I adaptable? You bet your ass I am. People say, “Give me a one-liner on the book. Is it, ‘Anything is possible?’ ” Anything is possible, given my background.

You’ve overcome extraordinary odds. Do you think your story is exceptional?

Am I the exception or the rule? Well, that’s the essence of what I think I have to share. Am I just unusual, or are there other aspects to it?

There are certain things you get by having a background like mine. Like adaptability, resilience, the ability to bounce back, perseverance. And gratitude and appreciation for having to earn what you have. There are advantages to having a challenging background. Luck is certainly a factor, and so is the context you find yourself in. I refused to accept the fact of my circumstances.

Some of my success was due to the fact that I had a certain innate talent. I had capabilities in engineering and math. But I also had a dream. I really wanted something, and I felt I could get it. I think some of these things can be learned. If someone like me can communicate that with kids, it can make their trip a little bit easier.

You arrived at Rochester in 1954 from an orphanage. Why didn’t you want your classmates to know your background?

When I came to Rochester, I decided to hide my life. I didn’t want pity. I didn’t want sympathy; I didn’t want to get something I didn’t deserve. It just didn’t do me any good. After the first year at Rochester, I decided I was really going to join campus life as much as I could. I got a crew cut, went down to a store in Rochester and bought a tweed jacket. The whole transition. I wanted to be accepted, so I made those changes, but people didn’t know the story.

For someone who wrote a memoir, you seem keen to look ahead rather than back.

I always tried to look ahead. People say to me, “Why didn’t you look for your mother?” When I was six years old, I realized she wasn’t there. Until I was 60, I thought she was dead. I had enough things to cope with, so actually it was a defense mechanism, in many respects. I didn’t realize what I was doing. In my business life, my magic two words are, “What’s next?” What are we going to do here to stay ahead of our competitors?

What’s next for you?

At the Nantucket Golf Course, we have a foundation that supports 40 to 50 charities on the island and has put 25 kids through college. Our newest effort is vocational scholarships for kids who want to become chefs, welders, carpenters, or pursue occupations that don’t require a four-year college degree. This is one of my new mini crusades since I believe vocational education is one of the solutions to our US employment problem. I may try to take our model to other clubs in communities like ours.

I also have a couple more books that I’m working on. One is focused on what I’ve often described as the importance of defining the “Four P’s” of your life—your passion, your principles, your partner, and your plans—but it’s really about the conversation you need to have with your inner voice. Your inner sense of yourself is one constant you have in your life, and you need to develop ways to keep going back to it and listening to it.

Do you have advice for listening to that inner voice?

Every year you should sit down and review certain characteristics that you have. I do that, and then every three years, I do a deep dive. It isn’t business strategy but personal strategy. Self, family, work, community—reviewing each one of those areas and saying, “Am I doing those things correctly?”

In my business life, I really tried to make sure there was a certain amount of balance. I had a goal of having a family. One of my legacies is having a family. Having three children and eight grandchildren is a pretty good deal. That’s a pretty special experience.

—Scott Hauser

After playing freshman basketball and baseball, I chose not to try out for the varsity teams.

Academics and extracurricular activities became more important to me, and I knew I didn’t have much of a future as a professional athlete. I played three years of intramural football, basketball, and baseball. Intramural sports gave me the opportunity to enjoy the camaraderie of being part of a team and the rush of adrenaline I got from competition—without the practice requirements of the varsity teams.

During my freshman year, I served on the integration committee, which was responsible for combining the women’s campus, called the Prince Street Campus, with the men’s campus, called the River Campus. At the time, the two campuses sat five miles apart. Even though the University had been admitting women since 1900, men moved to the River Campus upon its completion in 1930, and the women had been separate ever since. The integration was successfully completed in 1955. As a freshman I was rejected by all the fraternities—probably because of my appearance and because all but one fraternity didn’t take Jewish students. I didn’t think of my appearance as a big deal, but I guess it was. As my freshman year progressed, I cut my hair in a crew cut, bought some new clothes, and was helped by a residence-hall mate, Ed Kaplan, who lent me a few of his suits. Fortunately, he was exactly my size, and his father was a haberdasher. Another hall mate, a sophomore named Zane Burday, befriended me early on and counseled me on what to do and not do. His organic chemistry notebook was instrumental in getting me and a number of others through the course. He graduated Phi Beta Kappa, became a doctor, and was my internist for 30 years. He died a few years ago, and, as I said at his funeral, he did so much for so many but never asked for anything for himself.

In my sophomore year, my new look and campus activities resulted in my being pledged by Theta Chi fraternity, making me the first Jewish pledge in the 100 years of the organization’s history. My fraternity brothers were a great group of guys, and pledging was a real milestone for me. In my junior year, I became the social chairman, my job being to take charge of the events the fraternity held each Saturday night. During my tenure, I dreamed up a party for the month of February called the Beachcombers Ball. In all modesty, it turned out to be one of the fraternity’s best parties ever, and it became a tradition for a number of years.

I really enjoyed participating in projects that took me in various directions that I wouldn’t otherwise have explored. I was in all three honor societies; I was chairman of the University’s finance board, which distributed money for campus activities; I was one of 15 elected student government representatives; I was chairman of the engineering council; I was business manager of the dramatic society, responsible for filling the theater for every show; and I was a member of the yearbook staff. I was Mr. Involved!

In addition to everything else, in my sophomore year I got the idea to start a humor magazine modeled along the lines of The Harvard Lampoon.

It was called UGH (for UnderGraduate Humor), and it didn’t come into being until my junior year. Although I was seen by most people as a pretty serious guy, I also had, and continue to have, a very dry sense of humor. (As my wife, Barbara says, I’m not always fun, but I am funny.)

At the time, I thought the students could use an infusion of levity, especially my fellow engineers, who spent more time studying and working in the lab than anything else. The engineering program was tough on all of us, and a large number of students flunked out each year. In my junior year, when the magazine was launched, I was taking organic and physical chemistry plus a couple of other demanding courses. I had six 8 o’clock classes and a laboratory every afternoon.

To get the magazine started, I first put together a blue-ribbon group of students to help get the project approved by the president and deans, who were not really in favor of what they considered to be a frivolous project. The administrators were a little touchy at first because they weren’t sure what to expect. Was the magazine going to be farcical? Satirical? Would it mock “the system”? I gave the University every assurance that my goal was to entertain the reader and not embarrass the school, and the officials eventually gave us the green light.

Then the staffers and I went out and collected all the various humor magazines we could find from around the country. We studied the best features from each and adapted them to produce a prototype of the first issue.

As it turned out, I really liked entrepreneurialism—especially sales—and I still do.

To finance the publication of the first issue, we went to local merchants, knocking on the doors of every kind of establishment, from bars and hamburger joints to hardware stores and gas stations, all in an effort to sell them ad space. It was a risky buy for them because it was a new magazine with no track record to point to. We were selling enthusiasm—and passion. I learned a very important lesson that year: if you can sell something that does not yet exist to people you have never met before, you will have a leg up on life.

Luckily for us, there was obviously latent demand for humor on campus, since we sold out the first print run in 45 minutes. I got a big kick out of the fact that the librarian, who was originally not in favor of the project, later came begging for a few copies to put into the archives. Fortunately, I was able to save a few copies for myself and have held on to them to this day. Once you launch a startup like that, nothing else seems terribly hard. I discovered that when you operate on passion, it isn’t work. It’s pleasure.

Because I had nowhere to go during most summers and holidays, and because I needed the money, I worked multiple jobs during those periods.

My scholarship only gave me 50 dollars a month, so money was always tight. Working was a necessary means of survival. My jobs ranged from waiting tables to working in the college laundry, to removing railroad ties from an abandoned rail line. When I needed a typewriter in order to write my papers, I wrote to a manufacturer and offered to sell its products on campus if it would give me one as a sample that I could also use for my own needs. The manufacturer took me up on it, even though I only wound up selling one typewriter in two years. I also worked at a local foundry, the post office, and on a Saint Lawrence Seaway construction site. In my senior year, to earn extra income, I became a resident advisor in the dorms.

At one job I had during the summer between my junior and senior years, I waited tables at a Bob’s Big Boy restaurant from 6 p.m. until 1 a.m. When I got off work, I would sleep for a few hours, then head over to the University library, where I helped with various tasks during the day. It was a perfect job because when I wasn’t busy, I could doze off. One morning, however, the librarian caught me sleeping.

“Shhh. Don’t wake him. He works nights,” I heard her whisper to her colleague.

I will always remember what a kind lady she was.

Working all these jobs gave me the opportunity to test several career paths and meet all kinds of people. I discovered that we all have our own joys, our own passions—enthusiasms that inspire us to get out of bed every morning. Even more important, I understood that we can react the opposite way, too, in response to our own aversions. There’s great benefit in trying new experiences, especially when you’re young. Each job, each experience you have, moves you closer to your calling. And there’s no better time than college to experiment, to try new things, so you can become the person you were meant to be.

I had another life-altering epiphany that year. I realized that the more involved I got in extracurricular activities and the more groups I joined, the more my passion for science and math began to shift and turn into a keen interest in managing people. I felt as though this was truly my calling.

I loved putting projects and people together to solve a problem.

Even greater was my desire to help people do better than they believed they could do, just as I had been helped in the past by teachers and foster parents.

The University of Rochester has a motto, Meliora, which translates into “ever better.”

I don’t know if that motto rubbed off on me, but ever since I realized my calling, that philosophy has been something I have strived to inspire in others. It has carried into everything I’ve done. My unwavering drive for improvement motivated me to strive to be a little bit better than I was and then encourage others to do the same.

When you can lead people—whether it’s a group of 20 or a group of 2,000—to believe they are better than they think they are, they feel good about themselves and become more productive. That’s really what life is all about. If you can do that, ultimately you will have a success story to tell.

On a couple of Christmas holidays, I was invited to my classmates’ homes and gratefully accepted the invitations. My friends Dick Wedemeyer and Al “Jesse” James (yes, that’s his real name; he was my sophomore roommate) were particularly kind. But seeing them interact with their families was emotionally difficult for me. There they were, in the midst of a happy reunion, being so affectionate and having so much fun, which caused me to reflect on the lack of familial warmth in my own life.

Several months after launching the first issue of UGH, I went on a visit to the home of my good friend David Melnick—a year younger than I—who was going to be the next editor of the magazine. Of course, I wanted to pass on to him all the information he would need to take over the magazine, but I also enjoyed his company and wanted to spend time with him. While I was there, I met his younger sister, Barbara, for the first time. She was a pigtailed 13-year-old—seven years younger than I. To me, she was my friend’s kid sister. Cute, of course, but the thought never crossed my mind that we might someday become a couple.

Later I would learn that Barbara had a teenage crush on me from that very first meeting. She thought I was cute, too. And funny. But we wouldn’t see each other again until seven years later!

At the time of my first visit with the Melnicks, I was concentrating on more immediate concerns. I had a growing realization that by the end of my junior year, there would no longer be an enormous gap between where I was and where I wanted to go in life. In fact, I felt as though the brass ring was within my grasp. I could visualize my goal because I knew what I wanted. The mosaic of who I was had begun to take shape.

What I didn’t know at the time was how important it was to find the right life partner.

Sure, I had thought about getting married. I wanted the beautiful movie-star wife I saw on the big screen. I also wanted a white picket fence, a house in the suburbs, the whole package. In short, I wanted the life I never had, giving my children the love that I was denied. I wasn’t going to settle or compromise my principles until I could turn that vision into reality. But there were things I had to do first. I had to leave behind my college relationships because I just wasn’t ready. That dream would have to wait.

The essay is adapted from On the Road Less Traveled: An Unlikely Journey from the Orphanage to the Boardroom (Skyhorse Publishing, 2021). Copyright Edmund A. Hajim. Used with permission. All rights reserved.

From Leather Jacket to Board Chair: About Ed Hajim

Now the chairman of High Vista, a Boston-based money management company, Hajim has more than 50 years of investment experience, holding senior management positions with the Capital Group, E. F. Hutton, and Lehman Brothers before becoming chairman and CEO of Furman Selz.

In 2008, after 20 years on the University’s Board of Trustees, Hajim began an eight-year tenure as board chair. In recognition of his gift commitment of $30 million—the largest single donation in the University’s history—the Hajim School of Engineering & Applied Sciences was named in his honor.

Through the Hajim Family Foundation, he has made generous donations to organizations that promote education, health care, arts, culture, and conservation. In 2015, he received the Horatio Alger Award, given to Americans who exemplify the values of initiative, leadership, and commitment to excellence and who have succeeded despite personal adversities.