Professor Christopher Ritchlin, in blue sweater vest, is shown with members of his laboratory and clinical coordinator team. Ritchlin collaborated with more than a dozen experts from around the world on the first set of treatment recommendations for psoriatic arthritis.

Professor Christopher Ritchlin, in blue sweater vest, is shown with members of his laboratory and clinical coordinator team. Ritchlin collaborated with more than a dozen experts from around the world on the first set of treatment recommendations for psoriatic arthritis.

The first step: become part of a community of researchers

(This is part of a series identifying faculty leaders who have assembled teams to pursue large research awards or other projects, and explaining their approach and motivation in building a team.)

After

Christopher Ritchlin arrived at the University in 1991, eager to investigate a challenging disease called psoriatic arthritis (PsA), he would

travel to conferences where he was the only rheumatologist in a room full of dermatologists.

But he didn't let that deter him.

"I would present at these meetings. I would bring my posters. That's how I got started," said Ritchlin, a Professor of Medicine and Chief of the Division of Allergy, Immunology and Rheumatology. He forged connections with the dermatologists, and then with the rheumatologists he came across who were interested in PsA. "And then very quickly, once our research took off and we got some big papers in the late 1990s, the networking was very easy."

"For younger investigators it is important to

look for areas of interest that you have a passion for, find other investigators in other countries who share that passion, and start working with them. Good things will grow out of that."

That was certainly the case for Ritchlin.

Early in his career, he and other PsA investigators collaborated with Phillip Helliwell, a rheumatologist at the University of Leeds in England, on developing diagnostic criteria for PsA. That led to the formation of GRAPPA (Group for Research and Assessment of Psoriasis and Psoriatic Arthritis) — an international consortium of rheumatologists, dermatologists, radiologists, epidemiologists, and patient representatives — to expand research and treatment options.

PsA develops in about a third of psoriasis patients, resulting not only in skin plaques but various arthritic symptoms, including joint pain, inflammation of the spinal column, and painful, sausage like swelling of fingers and toes.

As targeted biologic therapies, especially tumor necrosis factor inhibitors, began to revolutionize treatment options for PsA, "it became apparent we needed to help clinicians around world figure out how to treat this disease (which affects as many as 600,000 people in the United States alone)," Ritchlin noted.

Along with Arthur Kavanaugh, Professor of Clinical Medicine at UC San Diego,

Ritchlin led a GRAPPA-sponsored project that drew upon the expertise of more than a dozen collaborators from around the world to establish the first ever set of treatment recommendations for PsA. This culminated in "Treatment recommendations for psoriatic arthritis," published in the

Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases in 2009.

Ritchlin was the first author.

"I didn't do it so much as a researcher, but as a clinician with expertise that I thought could help other clinicians around the world deal with this very challenging disease," Ritchlin explained.

This was not an NIH-funded project that brought millions into the labs of Ritchlin and the other investigators. GRAPPA covered costs of meetings and publication, but that was about it.

However,

Ritchlin's leading role in the GRAPPA project paid rich dividends for his research career.

"It always helps when you are regarded as a thought leader and as someone who helped develop international treatment recommendations for a disease," Ritchlin said. "It facilitates collaboration with other investigators. The people at NIH know you as someone who led a significant effort. And when you contact pharma (pharmaceutical companies) about doing investigator-initiated projects, they're very interested in talking to you."

The same pathways that helped propel Ritchlin's career are still there for young investigators, he emphasizes. If anything, the stagnation of federal research funding in recent years — and subsequent decline new physician-scientists — has heightened interest in making those pathways available to young investigators.

"In rheumatology we lack a whole generation behind me of mid level investigators," Ritchlin said. "This is a big problem. How do you draw people into research and build their confidence so that they can be successful? One way is to help them become part of a community that can provide strong mentoring and opportunities to extend young investigators' research into new areas."

"We (GRAPPA) are always looking for young investigators to mentor and encourage," Ritchlin added. "We have seed grants that have been immensely helpful in getting young people off to a good start." The organization's international network of collaborators fosters other opportunities, as well, such as exchanges of trainees. One of Helliwell's fellows, for example, is completing a year of study in Ritchlin's lab, learning how to use musculoskeletal ultrasound, a skill she will take back to continue her research in England.

There are any number of similar consortiums and organizations of researchers in other disciplines, eager to welcome young investigators, Ritchlin noted.

All they have to do is answer the call.

(Next: David Williams, a pioneer in using adaptive optics to correct vision, finds value in sharing his discoveries.)

Do you have an interesting photo or other image that helps illustrate your research? We would like to showcase it. Send a high resolution jpg or other version, along with a description of what it shows, to bmarcotte@ur.rochester.edu.

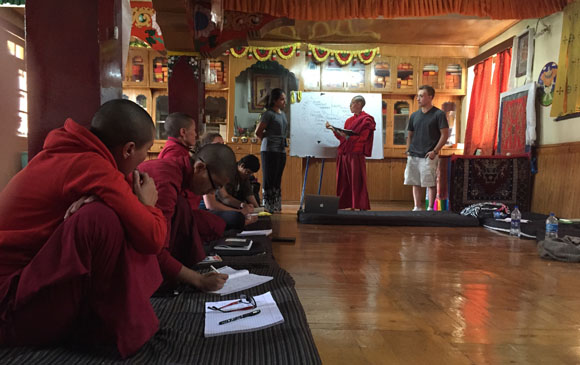

Sanuja Bose '16 and Michael Healey '16, who provided this photo, teach a group of nuns at the Ladakh Nuns Association in the city of Leh, India, about the public health process, part of a series of lessons and workshops held over the course of four or five days. The nuns then assisted Assoc. Prof. Nancy Chin's team of researchers in conducting a survey in Matho, a nearby village.

Sanuja Bose '16 and Michael Healey '16, who provided this photo, teach a group of nuns at the Ladakh Nuns Association in the city of Leh, India, about the public health process, part of a series of lessons and workshops held over the course of four or five days. The nuns then assisted Assoc. Prof. Nancy Chin's team of researchers in conducting a survey in Matho, a nearby village.

Good team dynamics pay off in the field

Long before they arrived in Borca di Cadore, Italy, and Ladakh, India, to conduct community health research this past summer, seniors

Jillian Dunn and

Shakti Rambarran were laying the groundwork.

Because of their experiences conducting research in those communities the previous summer with Public Health Sciences Prof.

Nancy Chin, they were designated as the research project coordinators for the three-week stays in each location.

To them fell the task of organizing weekly pre-departure seminars all last spring for 12 other undergraduates who had joined the team. The seminars included readings and discussions on anthropological data collection and analysis using a community engagement approach. They also were involved in making sure everyone obtained visas, and choreographing all the stopovers and accommodations.

"

There are a ton of logistics that go into something like this," said Rambarran, a public health sciences and psychology major.

"What really worked out well last summer is that we had

established good team dynamics," added Dunn, a public health sciences and philosophy major. For example, everyone was trained to take turns doing the various tasks involved in conducting in-depth interviews. "We really supported each other. When something didn't work, that made it easier to respond to it."

Rambarran witnessed that firsthand in Ladakh, when she fell ill and had to take a break from her duties. One of the other undergraduates on the trip promptly stepped forward and carried them out until Rambarran was back on her feet.

"It's one thing to say the people on your team are skilled individually and have great assets they can bring to the team, but if they don't get along, and don't trust each other — if they don't come to rely on each other — it doesn't work."

The research model used by Chin and her students stresses immersing themselves in the community — and engaging community members in every aspect of the research.

"It makes you more culturally aware, and calls you out on many of your assumptions," Rambarran said.

She was initially put off, for example, when she was trying to interview Ladakhi women during 2014, and their husbands would come up and start answering for them. She interpreted this as males being domineering; to the women, however, this was what they expected their husbands to do, to help protect them as they talked to a complete stranger.

Michael Healey, a senior in biology and public health sciences, eventually wants to be a physician and public health professional in international development work. As a result of his participation on the Borca team two years ago, and on the Ladakh team this past summer, he said, "I am no less motivated to do this kind of work, but I'm

more aware of the limitations I have as an American or westerner going into another country."

"You can't just go in and say 'here's what you have to do to improve your health; this is my prescription for your community.'

Everything you do has to be informed by their experiences, and by their culture."

"It really is a partnership."

(Click here to see photos of the people and places encountered by the undergraduate researchers in Ladakh last summer.)

URMC partners with company to create tissue bank for cancer research

The University of Rochester Medical Center has announced it is

collaborating with Indivumed, a Germany-based company, to establish a bank of human tissues and tumor samples that are expertly preserved and stored for use in cancer research.

The URMC signed a three-year agreement with Indivumed; financial details were not disclosed. Approximately 15 other research institutions have formed similar partnerships with the company—including Georgetown University's Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center in Washington, D.C., the Geisinger Health System in Pennsylvania, and several medical centers in Europe—enabling a worldwide network for researchers to access the biological specimens.

"Collecting and properly preserving human tissue is critically important to cancer research, but it's

difficult to fund and requires a specialized set of skills and expertise to build such a program," said

David C. Linehan, the Seymour I Schwartz Professor and Chair of the Department of Surgery, and director of clinical operations at the Wilmot Cancer Institute. Linehan will be the supervising investigator for the URMC-Indivumed partnership.

Read more . . .

The story behind NIH's emphasis on rigor, reproducibility

Starting in 2012, Brian Nosek of the University of Virginia began a project that would

attempt to reproduce the results of 100 psychology studies that had been published in three scientific journals. Enlisting the help of several hundred colleagues across the country, the scientists simply re-ran the studies described in the journals to see how many of them would match up to the results of the original publications.

Only 39 of them did.

Nosek's findings, published in the journal

Nature in 2015, are among the reasons that the National Institutes of Health are placing an added emphasis on rigor and reproducibility.

Click

here for a

CTSI Stories discussion of what the NIH requirements entail.

Introducing a new faculty member

Bin Zhang has joined the Department of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine and the Department of Pediatrics as an assistant professor. He maintains active research interests in RNA-based disease biology, cancer biology, and biomarker discovery using genomic approaches. In particular,

his research focuses on molecular classification of B cell lymphomas, and development of novel NGS-based methodologies for efficient circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) detection and nucleotide-level mapping of disease-associated chromosomal rearrangements. His study will help us

better understand genetics of both constitutional and somatic diseases and facilitate individualized/targeted patient care. He earned his BS in Biology from Sichuan University in China, MS in Biology from Truman State University, PhD in Molecular Genetics and Genomics and his Clinical Genomics training at Washington University in St. Louis. He completed his post-doctoral training at Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory studying function, regulation, and evolution of long noncoding RNAs.

University research in the news

An international research team, including

Jack Werren, the Nathaniel & Helen Wisch Professor of Biology, has successfully

mapped the genome of Cimex lectularius — the common bed bug. In his part of the sequencing project, Werren discovered 805 possible instances of genes being transferred from bacteria within the bed bug to the insect's chromosomes — a process called lateral gene transfer (LGT). "Usually, genes that are transferred from other organisms never become functional or are harmful to the host organism," said Werren. One exception involves the transfer of a patatin-like gene from the

Wolbachia bacteria. Patatin genes help organisms to store and cleave starch and lipid molecules. The gene, transferred from the intracellular bacterium

Wolbachia to

C. lectularius, appears to be functional in the male bed bug, but not the female. "

Because the inserted genes create unique genetic profiles in bed bugs, they have the potential of becoming effective targets for pest control," said Werren.

Read more . . .

University researchers have found that caring for others dips during adolescence. But

when young people feel supported from their social circles, their concern for others rebounds. "Young people often perceive relationships they have as being less supportive during middle and early high school years," said

Laura Wray-Lake, an Assistant Professor of Psychology. "Our study showed that youth perceptions of supports from parents, school, friends, and the community decreased across adolescence. Social responsibility — values that support caring for the welfare of others — declined in concert with these decreases in support."

Read more . . .

A team of Rochester scientists has, for the first time,

identified and isolated a stem cell population capable of skull formation and craniofacial bone repair in mice — achieving an

important step toward using stem cells for bone reconstruction of the face and head in the future, according to a new paper in

Nature Communications. Senior author

Wei Hsu, Dean's Professor of Biomedical Genetics and a scientist at the Eastman Institute for Oral Health, and lead author

Takamitsu Maruyama, Research Assistant Professor of Dentistry,

focused on the function of the Axin2 gene and a mutation that causes craniosynostosis — a skull deformity — in mice. Their latest evidence shows that stem cells central to skull formation are contained within Axin2 cell populations. The team also confirmed that this population of stem cells is unique to bones of the head, and that separate and distinct stem cells are responsible for formation of long bones in the legs and other parts of the body. One of their goals is to help scientists better understand and find stem-cell therapy for craniosynostosis in infants.

Read more . . .

Researchers at the School of Medicine and Dentistry have

uncovered the cell in the ovary that governs the timing of ovulation and plays a major role in fertility. This finding

could unlock clues to remedy infertility among people who have altered sleep schedules due to shift work or frequent jet lag, for example.

Michael Sellix, Research Assistant Professor of Medicine (endocrine/metabolism), found that

theca cells, which aid the development and release of eggs from the ovary, are important for maintaining a cyclic window of sensitivity to the hormone that incites ovulation, or egg release. Theca cells control the ovary's ability to respond to luteinizing hormone (LH) by ramping up production of the receptor for LH at precisely the right time. "We used to think that the clock in the brain told the pituitary gland what to do, which told the ovary what to do. Now, our data has shifted that paradigm to the idea that the clock in the ovary is as important for sensing what the brain is telling it as the brain is for telling it in the first place." Sellix hopes that this new knowledge will lead to

theca-cell-targeted therapies that may help women with disrupted circadian rhythms start a family.

Read more . . .

PhD dissertation defense

Sandhya Seshadri, Health Practice Research, "Understanding Community-Dwelling Older Adults' Experiences of Dysphagia and a Texture-modified Diet." 1:30 p.m., Feb. 12, 2016, Helen Wood Hall (1w-501). Advisor: Craig Sellers.

Mark your calendar

Feb. 9: Informatics, presented by Timothy Dye, CTSI director of biomedical informatics. Noon to 1 p.m., Helen Wood Hall Auditorium (1w-304). Part of CTSI Seminar Series.

Feb. 10: Noon deadline to apply for Center for Community Health mini grants to support the development, strengthening or evaluation of community-URMC health improvement partnerships for research, education, intervention, or service. For more information and the application form, see the "quick link" at the Center for Community Health

website.

Feb. 26: Deadline to nominate junior, tenure track faculty in natural or biological science departments for the Furth Award. Read more

here.

Feb. 29: Deadline to file initial applications for pilot project funding from the Infection and Immunity: From Molecules to Populations (IIMP) program.

Read more. . .

Feb. 29: Using online tools to save faculty time, a Technology in Health Professions Education Workshop. 11:30 a.m. to 1 p.m., Helen Wood Hall (1w-510). To register, contact

karen_grabowski@urmc.rochester.edu

Please send suggestions and comments to Bob Marcotte. You can see back issues of Research Connections, an index of people and departments linked to those issues, and a chronological listing of PhD dissertation defenses since April 2014, by discipline.