|

![[NEWS AND FACTS BANNER]](/URClipArt/misc/newsfacts.jpg) |

|||||||

Special Report

| ||||||||

|

| Phillips |

In early 1998, the University's endowment topped the $1 billion mark, an eye-catching financial achievement that called attention to Rochester's fiscal fitness among the nation's colleges and universities.

But as anyone who's ever puzzled over a 401(k) statement or who's tried to read between the lines of a corporate financial report knows, figuring out the "bottom line"-and what that bottom line means for a healthy financial future-requires calculations more complicated than simply adding up the numbers.

So, too, when it comes to a university's endowment, say Rochester's top money managers.

"Rochester alumni should feel good about the performance of the University's endowment," says Doug Phillips, senior vice president for institutional resources. "Like most top endowments, Rochester has benefited from the bull markets of the last decade.

"More important, the Board of Trustees' Investment Committee has put in place a strategy of diversification, disciplined asset allocation, rigorous benchmarking, and a prudent amount of risk-taking that allows the endowment to attain reasonable growth. That strategy will serve us well for the future, regardless of the overall trend of any particular market," Phillips says.

"But, relatively speaking, $1 billion is not a lot of money when you consider Rochester's standing as a world-class research university, the budgetary restrictions on how the endowment can be used, the changes in enrollment, and our Meliora aspiration of 'always better.' "

University

endowments, far from being the tweedy, bond-heavy wallflowers of the '50s and

'60s, have been making national headlines during much of the past decade. As

stock markets seemed to rise ever higher and as venture capital investments

were parlayed into staggering windfalls, reports of annual returns as high as

58 percent for a prescient few were not uncommon before the technology bubble

burst in the spring of 2000.

University

endowments, far from being the tweedy, bond-heavy wallflowers of the '50s and

'60s, have been making national headlines during much of the past decade. As

stock markets seemed to rise ever higher and as venture capital investments

were parlayed into staggering windfalls, reports of annual returns as high as

58 percent for a prescient few were not uncommon before the technology bubble

burst in the spring of 2000.

Even though the steam seems to have seeped out of most equity markets, the $1 billion club has hit record numbers. When the University topped $1 billion in 1998, it was one of only 34 colleges or universities in the ten-figure club. According to the Chronicle of Higher Education, at the end of fiscal year 2000, a record 41 colleges and universities could claim endowments valued at more than $1 billion.

As of June 30, 2001, Rochester's endowment stood at $1.2 billion, posting a slight positive return despite the overall downturn in U.S. equity markets during that fiscal year, a performance that topped the average of the University's peers.

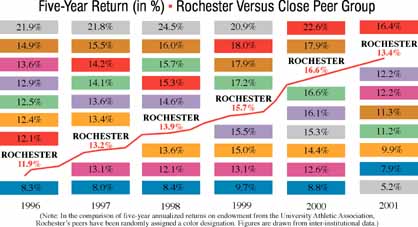

For fiscal year 2000, the University endowment's rate of return was 18.6 percent, compared to 15 percent for its peers. On a five-year annualized basis ending June 30, 2000, Rochester's rate of return was 16.6 percent, compared to 15.5 percent for its peers.

Phillips, charged with implementing the investment strategy set forth by the Investment Committee, joined the University in the fall of 2000 from Williams College. During his 14 years at Williams he helped guide the Massachusetts college's vault from a $200 million endowment in the mid-'80s to about $1.5 billion in 2000.

Rochester's steady-and respectable-growth in recent years is the payoff of a strategy adopted in the mid-'90s to mirror a diversification strategy first developed by endowment leaders at Yale University, Phillips notes. He credits the members of the Investment Committee, particularly chairman Edmund Hajim '58 and former University vice president Richard Greene, with taking steps to restructure Rochester's portfolio in line with the mainstream of top endowments.

"I

can't think of anything more fundamentally important than ensuring the endowment's

sound management," says Hajim, chairman and CEO of ING Aeltus Group. "The

management of the University's assets is an inter-generational challenge. It

needs to be strong and growing-not just for current use but for future generations."

"I

can't think of anything more fundamentally important than ensuring the endowment's

sound management," says Hajim, chairman and CEO of ING Aeltus Group. "The

management of the University's assets is an inter-generational challenge. It

needs to be strong and growing-not just for current use but for future generations."

Like other endowment leaders, Rochester has broadened its portfolio with carefully thought-out balances of domestic and foreign equities as well as investments in venture capital, hedge funds, real estate, and other assets that typically do not trade on public markets.

Working at Rochester with the Investment Committee and with the board as a whole, Phillips and the professional investment staff of the Office of Institutional Resources have implemented a series of benchmarking analyses designed to track Rochester's performance in comparison to those of the top endowments in the country and to those of Rochester's "close peers" in the original University Athletic Association: Brandeis, Carnegie Mellon, Case Western Reserve, Chicago, Emory, Johns Hopkins, New York University, and Washington University in St. Louis.

Currently, Rochester's portfolio is divided roughly into 70 percent traditional publicly traded assets-stocks and bonds -and 30 percent in nonpublicly traded investments, known in endowment management circles as "alternative investments."

Of the 70 percent in traditional assets, about 60 percent is in stocks (most with a value orientation and a portion indexed to the S&P 500) and about 40 percent is in bonds.

The alternatives include investments in venture capital, leveraged buyouts, real estate, hedge funds, timber, oil, and natural gas. While most alternative investments produce solid, predictable returns, some, such as venture capital, have the potential for tremendous growth.

It's a portfolio designed to provide above-average returns while maintaining significant hedges against the inevitable downturns in the traditional publicly traded markets.

"Stability, prudent risk-taking, and discipline in endowment management are critical because the endowment figures so prominently in Rochester's academic future," says Phillips. "Endowments are perpetual, intended to support institutions forever. So our investment time horizon has to match that infinite duration. We cannot veer off course in response to short-term changes in the public marketplace or domestic economy."

The goal is to keep Rochester's performance in the top quartile among large endowments and among the close peers of the UAA.

Rochester's good endowment performance should continue even after the events of last fall because of diversification," Phillips says. "It will probably never be the best-performing endowment in the country-there are certain risks we don't have the luxury to take-but we expect to rank in the top quartile of our peer group in most years."

A test of the strategy came late last winter. Analysts expect most endowments to post negative returns-some down more than 10 percent-for the year ending June 30, 2001.

Rochester posted a slight gain-about 1 percent-for the same 12-month period.

"Relative to our benchmarks, we are performing very well," says Phillips.

Long part of the financial structure of private (and many public) universities, endowments, through their annual spending, provide a source of operating income, student financial aid, and faculty salaries, among many other uses.

A typical strategy is to spend between 4 and 6 percent of the endowment's total value each budget year.

Rochester, like most universities, has had an up-and-down history when it comes to endowment growth. In 1849, when founding trustee John Wilder first persuaded a cadre of faculty and students to establish a university in Rochester, he hoped to raise $130,000-about three-quarters of which was earmarked for the endowment-to keep the enterprise afloat.

In 1932, George Eastman left the University $17 million in his will (bringing his total gifts to Rochester to about $50 million), which gave Rochester a significant leg up in the endowment race of the time. For much of the middle part of the century, Rochester was said to have the fourth largest endowment in the country.

As late as 1984, the University could still boast the eighth largest endowment. By 1991, Rochester's standing had fallen to 20th, the result of investment strategies in the '70s and '80s that limited the University's capacity for growth.

Rochester continues to feel some of those effects, especially in comparison to its peers, Phillips says, and the College is particularly affected.

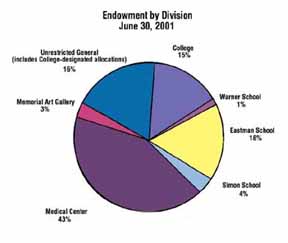

Although the total value of the endowment is about $1.2 billion, the allocation that generates support for the College (arts, sciences, and engineering) is only about $300 million.

In another comparison, Rochester's endowment, when divided by the number of students, is about $174,000 per student. Emory and Washington lead UAA schools with more than $400,000 per student. The nation's top endowment on a per-student basis is Princeton at $1.3 million per student.

Phillips points out that the best endowment strategy focuses on three areas: rate of return, spending, and giving. Of the three, rate of return accounts for only about 20 percent of long-term growth at most peer endowments.

Thanks to some of the enrollment strategies and cost control efforts implemented in 1996, the rate of spending at Rochester has stabilized, and alumni and donor giving has broken records the past two years, he says.

"In the history of endowment management, there has never been a better period of performance from equity markets than in the '80s and '90s," says Phillips. "The danger in expecting these returns to continue is that we might forget that the real source of endowment growth-as much as 75 percent to 80 percent over long periods of time-is gifts from alumni and friends."

Hajim agrees: "Critical to the endowment's future growth is ongoing alumni support."

"I truly believe that giving begets giving," Phillips says. "As alumni see that their money is well managed and as they see that their money goes to good programs, they feel good about giving to their alma mater."

He hopes to begin a series of new programs to tap into the expertise of Rochester alumni who have carved successful careers for themselves as money managers as well as other programs that would allow donors to have a greater sense of participation in Rochester's future.

| For more information, contact: Office of Institutional Resources 263 Wallis Hall P.O. Box 270012 University of Rochester Rochester, New York 14627-0012 (585) 275-3311 dphillips@admin.rochester.edu www.rochester.edu/endowment |

"We must communicate with alumni about how we are managing their endowment," Phillips says. "After all, they have entrusted us with their money."

That endowment-and its stable growth-will add up to more money for renovation, salaries, new facilities, and other academic needs that make Rochester a topflight university, Phillips says.

The success of Rochester's academic programs has created a resurgence in alumni interest in the endowment, Phillips says.

"The continuous growth of Rochester's endowment is critical to the University's future," he says.

"That's the message that I want to get out: I believe the best days are ahead of this institution."

Scott Hauser is editor of Rochester Review.

Maintained by University Public Relations

Please send your comments and suggestions to:

Rochester Review.

[an error occurred while processing this directive]