![[NEWS AND FACTS BANNER]](/URClipArt/news/titleNewsFactswide.jpg) |

||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

FeaturesMaster of the OperaDecades before his Lizzie Borden entered the repertory, Jack Beeson ’42E, ’43E (MM) was setting the stage for a distinguished career as a modern American opera composer. By Susan Hawkshaw ’68

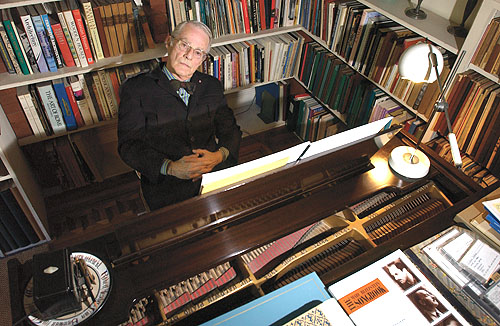

When composer Jack Beeson tells the story of his fascination with opera, he begins in 1933, at the age of 12, when he first sensed what he wanted to achieve in life. The stage was set for a lifetime of operatic composition when the youngster tuned in to the radio broadcasts of the Metropolitan opera in his family’s Muncie, Indiana, living room. “I was always listening,” says Beeson ’42E, ’43E (MM), best known for the modern American opera standard Lizzie Borden. “About that time, I decided that I would become a composer, but I qualified it by deciding that I would be an opera composer. “I remember very well that I had a small radio that I put on the right-hand side of the music rack, and across the other end of this long room was a large, old-fashioned console radio, so I had the tweeter, so to speak, on the piano, and the boombox on the other end. “I bought the Schirmer scores, and I would put one on the piano and sight-read it, accompanying the Met to the extent that I was able to.” Seventy years later, Beeson’s story has reached an unusually successful denouement. Now 81, the MacDowell Professor Emeritus of Music at Columbia University has earned a distinguished place in American music. His Lizzie Borden, which premiered in 1965, returned to the New York City Opera in a new production for a fourth season in 1999, making him one of the few living composers with an established work in the repertory. Even for a goal-focused composer like Beeson—he attempted his first libretto as a teenager—it’s a rare feat in the world of opera, where many works never receive a second performance. “Few contemporary American composers have grappled with the problems of composing for the opera stage as long and as hard as has Jack Beeson, whose works have been staged, televised, revived, and recorded with uncommon frequency and success,” music writer Duke Johns noted in the Music Educators Journal in 1979. “[His operas] have placed him firmly in a tradition of musically eclectic, dramatically cogent, and quintessentially American opera writing that has included such earlier composers as Virgil Thomson and Douglas Moore.” In the more than two decades since that summation, Beeson has continued to compose at a constant rate, working on operas, choral music, songs, and instrumental music. His catalog contains 131 works, including 10 operas—some chamber operas appropriate for smaller venues, and some large scale. His “conversational chamber opera in one-act,” Sorry, Wrong Number, based on an American radio play, was premiered in 1999 by the Center for Contemporary Opera in New York and was picked up last month by the Granite State Opera in Nashua, New Hampshire. Benton Hess, professor of voice at the Eastman School of Music and musical director of Eastman’s Opera Theatre, says such longstanding operatic success requires a rare combination of musical ability, talent, and theatrical sensitivity. He notes that such eminent composers as Schubert, Haydn, and Brahms failed to find lasting success in opera. “There’s just a handful of people who have managed to have pulled that off in modern opera,” says Hess, whose own first opera was premiered last year. “There have been some very, very good composers who have been miserable failures at opera.” Beeson attributes his facility, in large measure, to his time as a student at Eastman, where he studied orchestral writing with Bernard Rogers and took advantage of the opportunities provided by Howard Hanson’s groundbreaking Festivals and Symposia of American Music. “I might say that all of us who went to Eastman had an advantage nobody else did at that time and few do now,” he says. “We were encouraged to write for the orchestra and did so, partly because each year there was a symposium at which the orchestral works written by any student who was majoring in composition were read through and performed.” At Eastman, his contemporaries included other composers who would become prominent figures in American music: Jacob Avshalomov ’42E, ’43E (MA), William Bergsma ’42E, ’43E (MM), who rented a room from the Beesons at 2 Alexander Court, and Peter Mennin ’45E, ’47E (PhD). “Jack Beeson was the first friend I made upon arriving at Eastman, and ours is a friendship that has lasted six decades,” Avshalomov recalled recently. And in his recent book, he remembers, “In my first days in Rochester I was touched to be invited to dinner more than once by Jack Beeson. He was very talented, a good pianist, smart and studious. Although he was to write a number of piano sonatas, he knew early on that he wanted to be an opera composer. This was clear when I saw his many opera scores, not with soft bindings, but hardbound: He was in it for the long haul.” While at Eastman, Beeson met his wife, Nora Sigerist ’45, an English major on the Prince Street women’s campus. Both she and their son, Christopher ’72, chose Rochester, Beeson says, “so that they could get excellent instruction”: she in violin and he in piano. Beeson also took advantage of Eastman’s setting within the University to take arts and humanities courses. “At Eastman they thought I was nuts: What was I doing with a philosophy course—and taking English courses? But I was curious about things.” After graduation, Bela Bartok agreed to take Beeson as a student—a unique privilege, since the renowned Hungarian composer did not teach composition. In 1944, Beeson moved to New York and then joined the innovative Opera Workshop at Columbia. He taught at Columbia for half a century. As a faculty member, he served as chairman of the department and worked to establish a doctorate in theory and degrees in ethnomusicology. He is credited, along with other Columbia administrators, with launching the university’s doctor of musical arts degree in composition. Also at Columbia, Beeson’s wife, Nora, was the first woman to earn a Ph.D. in the Slavic languages and literature department. Their son, Christopher, died in a car accident during a hurricane in 1976. Beeson’s big break came when New York City Opera’s Julius Rudel accepted Lizzie Borden, after Beeson sang and played it at the piano. Nearly 40 years later, Beeson recreates the scene in an interview, singing the ship captain’s warm, lyric line from the first quintet while counting the rhythm—“Summer passes slowly at sea, two, three, four. . . .” Ralph Locke, professor of musicology at Eastman, says the opera has all the hallmarks for which Beeson has become known: clearly delineated musical identities for each character, lyric lines that are carefully composed so that the words of the libretto can be plainly heard, and a dramatic energy that keeps audiences intrigued. “Lizzie Borden is, I think, now one of the fairly standard repertory items of the late 20th-century American opera,” Locke says. “It probably will stay in the repertory for as long as people are performing opera.” At its premiere, Lizzie Borden, based on the story of the notorious Massachusetts ax-murderer, generated musical controversy—not so much for its protagonist, but for its sometimes dissonant musical idiom. Certain critics thought—mistakenly—that it used the 12-tone compositional technique associated with European composers Schoenberg, Berg, and Webern. Some questioned what a hymn tune was doing in that context. Such juxtapositions have become more common in recent years, Beeson says, as operas include both light and serious elements. “Such works tend musically and stylistically to combine, to alternate these two genres—as the back-and-forth changes occur in a given work,” he says. “I’ve written works which in terms of their own time are predominantly tuneful and consonant. And I’ve written works that are predominantly ‘tragic,’ and they, therefore, make use of the more extreme kinds of expression.” “Lizzie Borden is an example that includes both, dramatically: Hymn tunes sung by children, other things sung by children, by the simpler characters singing predominantly tunefully and tonally, and, in accordance with a woman murdering her parents, sections which are tragic and therefore, necessarily make use of the extremes of musical expression. “Such extremes change with the time,” he says. “In 1965, the passages were thought to be 12-tone by some well-known critics. Thirty-five years later, those passages were not nearly so extreme because they were more in the mainstream and taken without ‘ear medicine.’ ” One of Beeson’s most productive partnerships has been with highly regarded lyricist Sheldon Harnick (Fiddler on the Roof), a collaboration originally arranged in the 1970s by John Kander, once Beeson’s student and an assistant at the Opera Workshop, and now the composer in the celebrated Broadway team of Kander and Ebb (the duo responsible for Cabaret and for Chicago). “John kept saying to me that Harnick would be the perfect collaborator for me,” says Beeson. “John thought that people collaborating on a theater piece should be—if there are two—of different temperaments: That I tended to be rather sharp, ironic, intellectual, and brainy about things, which he supposed was all right, but I didn’t have any sentimental side; and that Sheldon Harnick was full of sentiment. This was a very good combination.”

The collaboration resulted in Captain Jinks of the Horse Marines, Dr. Heidegger’s Fountain of Youth, and Cyrano, Beeson’s most elaborate opera and the only one not on an American subject. Written over the course of 10 years in the 1980s, Cyrano (based on the heroic comedy by Edmond Rostand) was premiered in 1994 by the German opera company Theater Hagen. One critic termed it “a stunning theatrical event.” Harnick, whose first opera libretto was for Captain Jinks of the Horse Marines, recalls: “[Beeson’s] primary advice was: ‘Please don’t give me streams of expository text. Setting such text usually results in uninteresting music which I call “dial tone.” ’ Invaluable advice. “Then, like most of the composers I’ve worked with, he would ask for changes in the text I gave him in order to accommodate the shape of the music he was composing, both for musical and dramatic purposes,” Harnick says. “However, unlike most of my other composers, Jack, himself, sometimes supplied the changes he needed, providing text of such high quality that I unhesitatingly accepted it and shamelessly took credit for it. This made for a most happy collaboration.” While Beeson is reluctant to categorize his music in terms of specific styles—“Any composer who has written 10 operas will have written different kinds of dramatic pieces which require, according to me, different kinds of music,” he says—he has earned critical acclaim for finding the music to fit the atmosphere he hopes to create. Although initially, as in the case of Lizzie Borden, some critics focused on European influences, Beeson’s music is based in American literature and evokes American locales. The opening of Lizzie contains a hymn tune (with music by Beeson set to 19th-century text) resonant of New England. The setting is Fall River, Massachusetts, near the ocean—and Beeson loves the water. “That goes all the way back to the lakes in my teenage years, to sailing, because for 50 years I always had a sailboat,” Beeson says. In the “San Francisco” duet from the 1953 chamber opera Hello Out There, he captures the sense of a city on the ocean with only 13 instruments. The music, he says, “has just the right sort of chill.” Although he retired from full-time teaching in 1988, Beeson continues to write new music and to find new audiences. In February, the Gregg Smith Singers gave the premiere of Beeson’s Summer Rounds and Canons in St. Peter’s Church in New York. Smith, who has recorded several of Beeson’s choral compositions, is planning an all-Beeson CD. The premiere of his A Rupert Brooke Cycle, a collection of songs on the work of the English poet (1887–1915), will be given this spring by bass Kevin Maynor and pianist Richard Woitach ’56E (also well known as a vocal coach and conductor, especially as an associate conductor at the Met under James Levine). And Beeson continues to mentor composers and musicians, who acknowledge his craftsmanship, generosity, and support. Widely recognized composer Jorge Martin says he “happily took in all Beeson had to offer” on the issues of word setting, and says Beeson has a “sensitivity to words and language and every aspect of how they work and sit in the singer’s instrument.” Pianist Marc Peloquin has completed two piano transcriptions of Beeson’s music: one an aria from Dr. Heidegger, the other a tango from a small-scale work, or “operina,” called Practice in the Art of Elocution (1999). (Beeson got the idea for the operina while he was looking through his daughter Miranda’s books and came across an American turn-of-the-century actor’s manual with amusing poses.) The work, which features a singer in period costume rehearsing with her accompanist, was premiered by soprano Lynne Vardaman together with Peloquin in May 1999. They gave a second performance in February 2002 in honor of the composer’s 80th birthday. “One of the reasons I love playing new music is the involvement with the composers,” Peloquin says. “Beeson likes to be around young people. His piano writing is extremely clear and expressive; his solo piano music has a lyric sensibility. His humor is subtle—what I love about the humor is that you sometimes laugh moments after the funny line or event.” Soprano Vardaman, who also had a lead role in Dr. Heidegger, says, “Jack’s music, while challenging, is very vocal. As a composer he has seen to it that he knows what voices can actually do. This coupled with a terrific sense of language makes his works very satisfying to sing.” The psychological and emotional pull of music and its performance resonates deeply with Beeson. He enjoys recounting a role he clearly relished: playing the young husband—a spoken part—in his own My Heart’s in the Highlands (1970), based on a work by William Saroyan. The work was commissioned by the National Educational Television Opera Theater, directed by Kirk Browning. “I must say that I had this wonderful cowboy costume, and Nora came up to see some of the filming,” he says. “I was sitting in the control booth, with all these TV monitors, and Kirk was sitting there pushing buttons as they were doing scenes that I wasn’t in, and I was sitting there with my hat on. “I was there for about half an hour, and she didn’t recognize me. Sitting next to me. I had beads, too. As Douglas Moore used to say, ‘I’m really alive only when I have an opera in rehearsal.’ ” Susan Hawkshaw ’68 holds a Ph.D. in musicology from Columbia University. She is assistant director of the Oral History American Music Archive at Yale University. |

||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||

| ©Copyright 1999 — 2004 University of Rochester | ||||||||||||||||