Scholarship

The Bard’s Dark Doppelganger

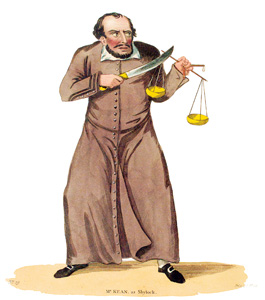

Shylock is more than a character: He is Shakespeare himself, says a noted literary critic.

By Kenneth Gross

Shakespeare’s Shylock thinks like a dramatic artist. He is Shakespeare’s double, in fact. Shylock is Shakespeare, a dark piece of self-revelation and dissimulation. He’s a way for the playwright to explore the ambitions and risks of his art.

We often remember Shylock in The Merchant of Venice as a figure set upon, as overcome by vengeful rage, as a puppet of hatred, as driven to seek a pound of flesh from a hapless Christian merchant. But he is also a self-conscious master of speech and masks, and a great maker of scenes.

Like Shakespeare, Shylock can take up and turn around other people’s words, play with their desires and fantasies. In the trial scene, where he pursues the forfeit of his bond, he’s able to transfix an entire audience with fear. Terrified at their own lack of control, Shylock shows his power to wield the laws they believed were theirs alone. Indeed, at moments, you can feel him turning the Venetians’ antisemitic slanders into dramatic weapons: With conscious art, he makes himself exactly the cruel, heartless, irrational, and opaque Jewish monster they expect him to be.

So Who Is Shylock?

Pop quiz: In which play does Shylock make his appearance?

While it’s easy to forget that Shakespeare’s Jewish moneylender is not the title character of The Merchant of Venice, says Ken Gross, professor of English, it’s not so easy to forget his long legacy in the popular culture of English-speaking countries.

The very word “Shylock”—a word that didn’t exist until Shakespeare gave it a voice—has been a racially charged stereotype for ruthlessness for the past 400 years.

“The character kind of outgrew the play that he’s in,” Gross says.

What explains that exceptionally long life, especially for a character who disappears before the end of the story that he does so much to propel?

In his new book, Shylock Is Shakespeare, Gross argues that Shylock’s longevity can be explained, in part, because his creator put a lot of his own personality, including his own insecurities, anger, and other psychological nuances, into creating Shylock. The resulting character is a psychologically rich and complex human being who took on a life outside the theater.

Both Shakespeare and Shylock, Gross says, are masters of manipulation and both revel in putting on a performance. And Shylock’s menacing and sarcastic undertone suggests that he, like Shakespeare, knows all too well the roles he is expected to play onstage and off.

“He’s one of the first characters in Shakespeare’s writing in which you are drawn to him through the combined intensity and ambiguity of his personality, by things that are often scarily unreadable, yet very concretely his,” Gross says. “There’s the sense that there is this entity called ‘Shylock.’

“I do have the sense that he’s a real breakthrough for Shakespeare.”

And what about the antisemitic overtones of the play?

Gross takes them seriously, recognizing that The Merchant of Venice has been staged to rally political sentiments across the spectrum.

But he says Shylock’s staying power draws from a multidimensionality that transcends stereotypes.

“By focusing on Shylock as a dramatic entity who somehow has a lot to do with Shakespeare’s idea of himself as an author, as a writer for the stage, as a manipulator of audiences—by focusing on that, you don’t suggest that the debate about antisemitism is irrelevant,” he says.“But you do focus on the strange wonder of the character.” “I want people to approach the character with more wonder and less fear,” Gross says.

—Scott Hauser

Shylock shares Shakespeare’s love for dark clowning at his own and others’ expense. Like a clown, he turns his powerlessness and humiliation to his dramatic advantage. And Shylock has a blunt, arresting eloquence that can both flatter his audience and put it in its place.

Shakespeare wasn’t particularly interested in Jews when he set out to write this character. He wanted to achieve certain theatrical effects by using the inherited figure of the usurious, conniving, manipulative Jew, partly following the example of Christopher Marlowe in The Jew of Malta. The character grew under his hands, energizing his comedy and simultaneously throwing its structure off balance. If some sympathy for the victim of abuse played a part, his sense of the character’s dramatic potential was even more important. The poet must have been drawn by Shylock’s reactive rage and sense of play, his way of provoking and laying bare the hatred of others. This was particularly attractive because it let him externalize—and set at a distance—something about his work for the stage. He even found a name that echoed his own.

Shylock and Shakespeare are both professional gamblers, as a critic once said. They play with loaded dice and carry out their contracts to the letter. They are pitiless, even in their generosity. They both deal in strange promises, “merry” bonds with hidden stings; they are both profiteers of loss, of human wanting. Shakespeare breeds binding words as mysteriously as Shylock says he breeds gold and silver. And both create terrible scenes that hold up mirrors to the needs and fears of their listeners, even as they both expose and conceal their own needs, fears and sense of loss.

Staging Shylock helps Shakespeare imagine the profits and potential costs of his hazardous game—being the kind of dramatist he is or aspires to be. He does something similar, if less extreme, with such doubles as Prospero and Hamlet. In particular, the figure of Shylock allows Shakespeare to express his veiled antagonism with that audience to which he is inescapably bound, especially his contempt for its strange marriage of passivity and power, love and treachery. In the end, both Shylock and Shakespeare want more than money for their plays. They want their hearers’ hearts out. They want their blood. The attempt almost costs Shylock his life.

Our wrestling match with a figure like Shylock is endless. He has entered into our common speech and cultural memory. Actors continue to test themselves in the role. Indeed, Shakespeare’s imaginary Jew has become part of the modern history of the Jews, and part of the history of antisemitism—his words of protest and his words of malice echo through later literature, sometimes in unacknowledged ways. (See John Gross’s Shylock: A Legend and Its Legacy for a fine exploration of the subject.) So the debates about whether the play is antisemitic or sympathetic to Jews won’t soon resolve themselves.

But we need to reflect on why the playwright invested so much dramatic energy in this character. To consider that his power, and thus his survival, depends on Shakespeare’s identification with Shylock may help us see differently what we’re arguing about. This intuition makes the character’s afterlife even stranger, because whatever we think of as Shylock’s Jewishness—whether we take this as sympathetic or slandered in the play—remains so bound up with the hidden pressure of Shakespearean histrionics and ambition.

Seeing this link might let readers approach this troubling play with more wonder and less fear. How this thought would change what actors do with Shylock I can only imagine.

Kenneth Gross is a professor of English at the University. His book, Shylock Is Shakespeare, is published by the University of Chicago Press. A version of this essay originally appeared in the London Times Higher Education Supplement (www.thes.co.uk).