Tribute

Arthur Kornberg ’41M (MD): 1918–2007

Before I had ever met Arthur Kornberg ’41M (MD), I had a distant connection to him through my father. It turns out that they were born weeks apart and attended Abraham Lincoln High School in Brooklyn.

When Dr. Kornberg won the Nobel Prize in 1959, I was 7 years old. I still remember my father telling me: “I’m not surprised. He was the smartest kid in the class.”

At the time, Lincoln was a brand-new school, and my father always told me that his was Lincoln’s first graduating class. When I finally met Dr. Kornberg, I related this story and he smiled, correcting me: “I finished high school early,” he said. “Actually, I was the first graduating class, a class of one.”

Dr. Kornberg was certainly in a class by himself. And when he died on October 26, at the age of 89, it had long been clear that his pioneering work was fundamental to contemporary “genetic engineering” as well as other medical applications.

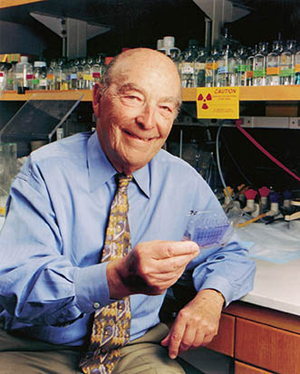

NOBELIST: Kornberg received the 1959 Nobel Prize in Medicine.

But it was also clear that, to Dr. Kornberg, the miracle of genetic engineering was not its enormous impact on agriculture, medicine, industry, or even Wall Street, but its illumination of biology.

As a student in the public schools of Brooklyn, the future Dr. Kornberg was a gifted student. Despite his academic achievements, college may not have been financially feasible were it not for the tuition-free City University system in New York City.

He attended City College, earning a B.Sc. in 1937 at age 19, followed by an M.D. from Rochester. During medical school, he discovered that he had mildly elevated bilirubin and he conducted assays of fellow students to determine the prevalence of this condition. The results were published in 1942—Dr. Kornberg’s first research paper.

After medical school, Dr. Kornberg completed an internship at Strong Memorial Hospital, and then joined the U.S. Coast Guard, serving as a ship’s doctor.

According to his family, as a result of his paper on jaundice in medical school, he was transferred from his ship to the National Institutes of Health, where he was asked to study a jaundice outbreak. The reassignment, he told his sons, changed his career from clinical medicine to research.

Although he also made several fundamental discoveries about the actions of vitamins, he gradually became fascinated by enzymes. During this period, he also became fascinated with Sylvy Ruth Levy, whom he married in 1943.

Sylvy was a double-alumna of the University, receiving a B.A. from the College in 1938 and an M.S. in biochemistry from the School of Medicine and Dentistry in 1940.

Sylvy also became a biochemist of note, and on the day that Dr. Kornberg was awarded the Nobel Prize, she was quoted in a newspaper as saying “I was robbed!”

In 1946, Dr. Kornberg joined the laboratory of Severo Ochoa with whom he later shared the Nobel Prize, and in 1953, he moved to St. Louis to become professor and chair of the Department of Microbiology at Washington University.

It was in St. Louis that he conducted his Nobel Prize–winning work, isolating a DNA polymerizing enzyme, the first enzyme to take direction from a template, now known as DNA polymerase I. (Arthur’s son, Thomas Kornberg, discovered DNA polymerases II and III in 1970. Another son, Roger Kornberg, was the 2006 Nobel Laureate in Chemistry for unraveling the 3-dimensional structure of RNA polymerase.)

In 1959, he was recruited to Stanford University to establish a department of biochemistry on the Palo Alto, Calif., campus.

What kind of man was Dr. Kornberg? Jay Stein, who re-established Rochester’s connection with Dr. Kornberg at the time that Dr. Stein was senior vice president for health affairs, remembers him this way:

“Shortly after I arrived in Rochester, a senior development officer, Roger Latham, came to see me and urged me to go meet Arthur Kornberg. Up to that point, I hadn’t even realized that Arthur was a University of Rochester graduate and had no idea of the early stories of how our most famous alumnus had been shunned because he was Jewish. We now had Goldsmith, Goldstein, and Stein in charge of the Medical Center, i.e., things had changed. . . This began a wonderful friendship with this remarkable man.

“The culmination was his agreement to have the first new research building in the Medical Center named for him. He was so thrilled that he reached into his drawer and handed me his Nobel medal [and] asked us to put the medal in a nice place for the public to see, and it resides in the foyer of the Kornberg Building today.”

Dr. Kornberg’s first wife, Sylvy, died in 1986. He married Carolyn Dixon in 1998. In describing her late husband, Carolyn emphasized his marvelous love of life, his brilliance, and his sense of humor. She said that as he became more “seasoned” in his later years, he “became universal. He always had time for everyone—students, sons, grandchildren, faculty, friends, post-docs.

“Sometimes faculty who wanted to see Arthur had to wait in line while he would be chatting with someone in his office who was ‘unscheduled,’ but this is who he was.”

The Kornberg Medical Research Building of the University recognizes and honors the life and scientific achievements of Dr. Kornberg.

“Kornberg,” our shorthand name for this research facility, inspires those who work within it to reach for path-breaking, paradigm-shifting science worthy of its namesake.

—David Guzick

Guzick is dean of the School of Medicine and Dentistry. This essay is adapted from one he wrote for his regular newsletter. To read Guzick’s newsletters, go to www.urmc.rochester.edu/SMD/about/newsletter.cfm.