New Ways of Seeing Images

Collaboration between the College and the George Eastman House is bringing a new focus to historic images and how to access them.

By Kathleen McGarvey

When computer scientist Christopher Pal looks at the teeming, formless array of images available on the Web, he doesn’t see disorder. Instead, he sees a chance to redefine how people access photographic archives and how scholars and others share information about historical images.

“We have so many images online and so many people tagging them—we’re awash in billions of images, and we can leverage them for a goal: exploring historical archives,” Pal says.

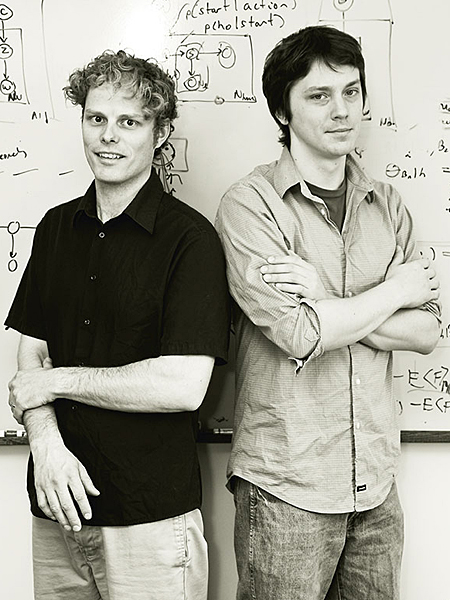

SOURCE IMAGE: The ability to capture detail in historic images is a byproduct of a process used for image preservation that has provided a valuable research resource for Rochester’s Christopher Pal (left) and doctoral student Nicholas Morsillo.

Reaching that goal is the aim of Pal, an assistant professor in the Department of Computer Science, and his team of researchers. In Pal’s workspace on the seventh floor of the Computer Studies Building, they are leading a three-pronged research attack that could alter how users from the most sophisticated scholars to the most snapshot-happy novices store, search for, and retrieve images.

A former scientist at Microsoft Research and the University of Massachusetts Center for Intelligent Information, Pal joined the faculty of the College of Arts, Sciences & Engineering last fall. Since then, he launched three interrelated research projects focused on images: 1) he’s fine-tuning a Web-based interface to allow people to access and navigate extremely high-resolution images; 2) he’s creating a tool for collaboratively annotating digitized images; and 3) he’s developing a system for teaching computers to recognize images much as humans do, so that Web-based image searches can soon be as sophisticated and fruitful as text searches are today.

“It’s a semantic image search on an unprecedented scale,” Pal says of the third arm of his efforts, research he is carrying out with doctoral student Nicholas Morsillo.

>

DETAILED VIEW: The corner of State and Main streets in downtown Rochester, N.Y., is a hub of activity in this daguerreotype taken around 1852. At right, the image is divided into tiles and photographed with a microscope. The technique, developed at Rochester’s George Eastman House, yields details rarely seen in such images.

Such work represents a “flagship project”—in the words of Thomas DiPiero, senior associate dean of humanities in the College—of a new relationship between Arts, Sciences & Engineering and Rochester’s renowned George Eastman House International Museum of Photography and Film.

The partnership, part of the College’s strategic plan, is designed to pair the University’s research prowess with the museum’s peerless resources.

“The collections at the George Eastman House are unparalleled,” DiPiero says. “The possibilities for collaboration are enormous.”

“We’ve only just begun our conversations, and already colleagues at George Eastman House and the University of Rochester have broken new ground on behalf of the science and art of photography and film,” says Anthony Bannon, director of the Eastman House.

Carried out in conjunction with conservators and curators at the museum, Pal’s research demonstrates not only a confluence of scientific endeavor and material resources, but also a kinship between pioneering technologies born a century and a half apart.

That’s because Pal, in developing 21st-century approaches to information processing, is working with a groundbreaking 19th-century form of information gathering: the daguerreotype.

One of the earliest photographic technologies ever developed, daguerreotypes were state-of-the-art in the 1840s and 1850s. Named for their French inventor, Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre, they are highly detailed images created on copper plates coated with polished silver.

With roughly 4,000 daguerreotypes, the Eastman House collection is one of the world’s largest.

“The daguerreotype was the first commercially successful photographic process and creates a unique positive image that is not reproducible,” says Ralph Wiegandt, assistant director of conservation education at the Eastman House. “Also, daguerreotypes are usually the first photographic images of a place or person.”

Because of the unusual materials and process through which daguerreotypes were created, they pose exceptional challenges for photographic conservators.

“The image surface is very sensitive to wear and, like any silver, it tarnishes.” Wiegandt says. “We don’t really understand its material surface, or how it responds to environmental agents and its own chemicals.”

In a pilot project supported by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, Eastman House conservators, in conjunction with those at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, have developed a method of monitoring daguerreotypes, a “non-perturbing” technique that does not expose them to further damage through excessive handling.

The conservators “photograph” the daguerreotypes with microscopes, creating a series of tile-like images that a computer can then stitch back together to provide a highly detailed view of the daguerreotype’s surface.

“It allows us to use the object itself to measure changes through time,” says Patrick Ravines, a senior researcher in the Eastman House’s advanced residency program in photographic conservation.

Even before meeting the microscope, daguerreotype images are arresting for their clarity.

With a level of resolution that permitted daguerreotypists to capture scenes and sitters in minute detail, the images, when viewed with the aid of a microscope, transport modern-day viewers to a past with a hitherto-unknown richness.

“You’re able to go deeply into a place, and see details I don’t think anyone has seen before,” Wiegandt says.

What he calls “the great fascination of being able to fully pull out the details” is a byproduct of preservation efforts, but it has provided Pal with a remarkable resource for his research.

As Pal, assisted by undergraduate research assistant Lam Tran ’09, develops methods to make such vast images—between 100,000 and 150,000 pixels—viewable on the Web, he’s forging a path to make widely available pictures of exceptional “historical, national, and market value,” according to Wiegandt.

Working with images from the Eastman House’s collection of photographs by Lewis Hine, an early 20th-century photographer known for, among others, his images of workers on the Empire State Building, Pal is creating a system by which people from a broad array of backgrounds can mark information about images.

“It will allow researchers from anywhere in the world to collaborate,” DiPiero says. “They can mark up the images according to their specialty.”

When experts in many fields can gather together, at least virtually, to examine an object of common interest, DiPiero says “it will change the way the disciplines inform each other.”

But for such a system to work, scholars must be able to search images efficiently.

Pal is on the trail of that innovation, too. By harnessing the sheer number of images available on the Web, he, Morsillo, and Randal Nelson, associate professor of computer science, are creating a way to teach computers to recognize images, and thereby group like objects together in a search.

“We’re laying the foundation that will allow us to build a system where we can find any object in an image, eventually,” Pal says.

“Chris Pal has shown there’s a pathway for the Eastman House and the University to work together,” Wiegandt says. “It’s a first step, and it has come about in an organic fashion, through finding areas of common potential.”

One important such area is the sciences. Photography, Wiegandt points out, blends art and science.

And while conservators at the Eastman House are among the world’s experts in photographic preservation, they find themselves increasingly turning to leading-edge science in their conservation efforts.

“We need people to be brought into our world who have highly specialized scientific skills that we don’t have,” he says. “And we have something to offer them.”

In fields such as physics, chemistry, optics, computer science, and medical imaging, the University and the Eastman House have created several ways to link their work.

Both institutions together administer the Selznick Graduate Program in Film and Media Preservation, a two-year master’s program in film restoration and preservation. In addition, the University and the Eastman House have begun work on establishing a master’s program in photographic preservation and conservation.

Also being explored are opportunities for a master’s degree or graduate certificate in material culture, the study of societies through their everyday physical artifacts; and opportunities for increased ties between the Eastman House and the University in studio arts and undergraduate film and media studies. Possible Eastman House involvement in some Memorial Art Gallery efforts is under exploration, too.

Between the University’s research strength, the museum’s resources, and the commitment of both to education, “it’s a perfect storm of collaboration,” DiPiero says.

And, as Wiegandt notes, it comes at a pivotal, even poignant, moment in the history of photography and film.

“The demise of traditional, or ‘chemical,’ photography and the recognition that an era is passing before our eyes,” he says, “has fueled interest in the history of photography, the process, the preciousness of the early image, and the wonderment of the technical achievement by the lay person mastering complex photochemical reactions in the middle of the 19th century.”

It’s not laypeople, but experts like Pal, Ravines, and Wiegandt who are keeping the work of the last century’s photographers well preserved and newly available.

“The Eastman House is really a national treasure,” says Pal. “It gives me a lot of satisfaction to be developing innovative ways to give scholars and the general public more access to these important technological, historical, and cultural artifacts.”

Kathleen McGarvey is an associate editor of Rochester Review.