Features

SLIDING SCALE: Experts say societal changes—such as ensuring all children, like Rochester preschooler Caedon Coons, have opportunities to exercise and safe places to play—are key to addressing obesity. (Photo: Adam Fenster)

SLIDING SCALE: Experts say societal changes—such as ensuring all children, like Rochester preschooler Caedon Coons, have opportunities to exercise and safe places to play—are key to addressing obesity. (Photo: Adam Fenster)When Paula Edwards, a mother of three sons who lives in Rochester, took her 12-year-old to the pediatrician for a check up, she learned something she hadn’t foreseen: her middle son was obese.

He would look at himself in pictures and remark that he was big, his mother recalls, but neither she nor he realized his weight had entered the realm of obesity. He was, in other words, part of a national epidemic, one that the University—with a range of community partners and a combination of outreach, clinical, and academic efforts—is working to address.

Edwards and her children—including an 18-year-old son and another son, just 3—snapped into action. She enrolled the family in the Healthy Hero Outreach Program, a project promoting healthy eating and active play that’s run by the University’s Center for Community Health. Since completing the program in August, Edwards’s son has lost 11 pounds, a loss she credits to the whole family making healthier choices—and to the planning that makes healthy choices viable when convenience beckons.

As a single mother with a full-time job as a social worker, a full course load as a student at Keuka College, and an active role in her community, Edwards found her time stretched thin.

“My kids ate a lot of fast food. I thought as long as they ate, we were doing okay. But then I saw the effects in my 12-year-old.”

Now the family cooks together, incorporating more fruits and vegetables into their diet, making trade-offs for treats, and choosing simple dinners some nights to give them time to go to the gym. When exercise has to be squeezed in, Edwards jumps rope while waiting for the bus with her son—something she says he views with a little chagrin. “It’s not always easy,” Edwards allows. But her motivation is strong. “I want to see changes in me—but I really want to see changes in my kids.”

“You see it. You know it,” she says of her son’s gradual weight gain. “But you don’t think it’s a real problem.”

She knows now that it is.

Though tobacco use is the leading cause of preventable death nationwide, obesity is gaining ground and may eventually overtake it. In September, the Trust for America’s Health and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation issued a report predicting that, if current trends continue, by 2030 all 50 states will have adult obesity rates above 44 percent, and 13 states will have adult obesity rates above 60 percent.

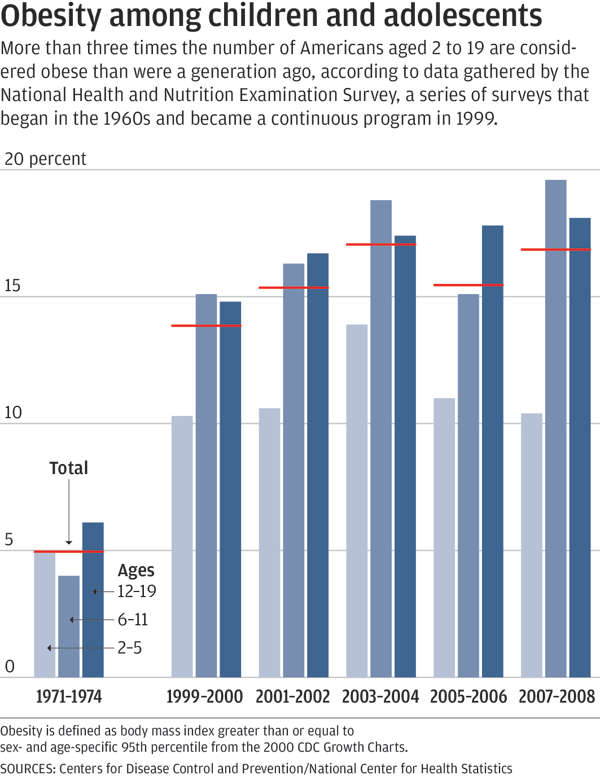

Tomorrow’s adults, of course, are today’s children, and the statistics are already alarming. Twelve and a half million children in the United States—about 17 percent of those aged 2 to 19—are considered obese, triple the number of a generation ago, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). In Rochester’s Monroe County, the figure is just slightly lower, at 15 percent. Include those who are overweight, between the ages of two and 10, and the number of those affected rises to a third. And for the first time ever, the rising generation of Americans faces the prospect of a shorter life span than that of their parents.

“It’s arguably our most important health problem,” says Jeffrey Kaczorowski ’91M (MD), associate professor of pediatrics and president and chief children’s advocate at the Children’s Agenda, an independent nonprofit advocacy organization dedicated to improving the health and education of children in the Rochester community.

And while parents like Paula Edwards see the threat of obesity playing out within their own families, the roots of the problem spread deeply and broadly, say experts.

“This isn’t about the kids or their parents,” says Kaczorowski. “It’s about the community and how the environment has changed since the 1970s. People talk about weight being a matter of personal responsibility and blame kids and families. And that’s not right.”

CHECKING IN: Pediatrician Stephen Cook checks the weight of 12-year-old Tyshawn Jones of Rochester. “Too often, obesity is presented as a health condition of choice,” Cook says. (Photo: Adam Fenster)

CHECKING IN: Pediatrician Stephen Cook checks the weight of 12-year-old Tyshawn Jones of Rochester. “Too often, obesity is presented as a health condition of choice,” Cook says. (Photo: Adam Fenster)Philip Nader ’62M (MD), ’63M (Res), a noted authority on childhood obesity prevention and a professor emeritus of pediatrics at the University of California at San Diego, agrees. “It’s taken complex changes to the environment to bring this epidemic about.” In December, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation released a study indicating that some cities and states are beginning to see small declines in their childhood obesity rates. It’s happening in places with focused strategies for addressing obesity, says Stephen Cook ’07M (MPH), associate professor of pediatrics. Rochester is in the process of collecting its own most recent statistics but has developed such strategies o

ver the last five years, mobilizing a grassroots campaign to change its environment and improve the health of its residents. The Greater Rochester Health Foundation (GRHF)—an independent community foundation established in 2006 to improve community health by providing funding to local organizations using the best evidence-based practices in community health—serves as the hub of a wheel made up of an array of community partners, including the University, the YMCA, the Rochester City School District, and the Finger Lakes Health Systems Agency. Edwards, too, has taken up the community effort, working with the GRHF to establish a healthy-weight program for children at her church.

In 2011, the CDC awarded the Medical Center, the Monroe County Department of Public Health, and a wide range of community partners a five-year, $3.6 million Community Transformation Grant. The funding is being used to develop Health Engagement and Action for Rochester’s Transformation (HEART), a comprehensive initiative to improve the health of county residents by creating an environment that supports healthy behaviors. Rochester is one of just 15 communities nationally to have received such a grant.

The funding came through the Affordable Health Care Act, as has another grant for the Greater Rochester Obesity Collaborative, which has been selected to serve as a national model for obesity prevention and treatment.

“One of the wonderful things about Rochester is the level to which people are willing to partner and collaborate around pressing health problems,” says Kaczorowski. There are relatively few communities, he says—among them, the city of Chicago and the state of Maine—that have tried to combine a community and clinical approach, as Rochester has.

Doctors are critical in preventing and treating obesity, he says, “but we won’t turn the tide without a strong level of community advocacy, policy, and programs.”

It’s an approach that has a strong history not only in Rochester but also in the foundation of pediatrics itself. In the late 19th century, Abraham Jacobi, regarded as the founder of American pediatrics and a tireless champion of public health, addressed the climbing mortality of New York City children due to tainted milk not simply by treating the children as they became ill but by working to protect them from infection in the first place. Through his “Safe Milk” campaign, he urged parents to boil milk until bubbling and worked with philanthropist Nathan Straus to provide milk sterilization stations throughout the city.

“That’s getting to the heart of what pediatrics is all about as a profession,” says Andrew Aligne ’01M (MPH), assistant clinical professor of pediatrics. With Kaczorowski, he codirects Pediatric Links with the Community, a program that teaches medical residents how to operate effectively beyond the examination room—as advocates in the community for their patients’ health. It’s an outgrowth of the biopsychosocial model of medicine developed at Rochester.

“Doctors work at the individual level. But if you want to move the needle on big public health problems, you need to act at the community level,” Aligne says.

The first step is for communities to do what they can to stop children from being overweight and obese, says Nana Bennett, professor of medicine and director of the Center for Community Health. “Childhood obesity is a classic prevention issue, because really the way to address it is to keep kids from putting on excess weight from day one.”

And prevention takes vigilance, says Nader. Parents looking at children often don’t see them as overweight. In a three-year-old girl, it takes only four to six extra pounds for her to be considered overweight, he says.

The road to weight problems can begin even before birth. Babies gain significant body weight in the final trimester in utero, and when that weight gain is too much—known as fetal overnutrition—the child can be set up for excess weight through infancy, childhood, adolescence, and on. Nader calls it a “snowball effect.”

“Once weight is put on, the body hangs on to it tenaciously. It’s a lifelong battle,” he says.

REAL FOOD: Jamal Jennings chooses an apple for his three-year-old daughter, Tanya, at Rochester’s Freedom Market, a source for healthy food in the city’s Beechwood neighborhood. (Photo: Adam Fenster)

REAL FOOD: Jamal Jennings chooses an apple for his three-year-old daughter, Tanya, at Rochester’s Freedom Market, a source for healthy food in the city’s Beechwood neighborhood. (Photo: Adam Fenster)Researchers point to measures, such as breastfeeding, that can make a difference right from the beginning.

“It’s very hard to overfeed a breastfed baby,” says renowned breastfeeding medicine expert Ruth Lawrence ’49M (MD), professor of pediatrics and neonatology. Research suggests that breastfeeding is in some way protective against excess weight gain, though scientists don’t yet know why. Lawrence and colleague Cynthia Howard ’97M (MPH), associate professor of pediatrics, say it may be related to the fact that babies learn more about satiety from breastfeeding than they do from bottlefeeding.

Between ages three and five years, the body is adding new fat cells—and does again in adolescence as well as, for women, during pregnancy—and those cells “just provide one more cellular home for weight later on,” Nader says. In other words, preschool “puppy fat” isn’t something just to be grown out of: it’s actively priming the body for later weight problems.

At the level of biology and socialization, a child’s early years set a path for future health. “Day-to-day behavior has a lot to do with what we did in our early lives,” says Kaczorowski.

Cook, who leads the Greater Rochester Obesity Collaborative, says a multitude of factors converge to make us, and our children, heavier. “We move less. We have more opportunities to eat. What we eat is bigger, tastes better, and has more calories. It’s even more dense—an ounce of bagel 40 years ago actually had fewer calories than an ounce today.” Coauthor of the first national paper to document metabolic syndrome—a clustering of risk factors that puts people on the path toward heart disease and diabetes—in youth, he last year was named Science Advocate of the Year by the American Heart Association for his work engaging lawmakers in issues related to heart disease and strokes.

“Too often, obesity is presented as a health condition of choice. And that’s not true,” he says.

Bonnie DeVinney, vice president and chief program officer of the GRHF, can outline some of the factors working against children’s maintaining a healthy weight: “The intense marketing of unhealthy foods. The growing tendency to eat more and more—and not just ‘supersized’ portions. The ‘normal’ size is bigger than what we had growing up.”

Children also spend less time playing outdoors than they used to. Part of the reason is the allure of television and computers—devices that lead kids to be sedentary. But while that hazard is obvious, another is even more dangerous, says Cook. Screen time exposes children to avalanches of advertising for cheap, calorie-laden junk foods, teaching them to ignore the dictates of hunger and eat as a form of recreation. Advertisers target young children. According to the New York Times, cereal companies alone spent $264 million in 2011 to advertise cereals targeted at children.

Part of the answer is education, as parents like Edwards have found. Adrian Elim ’13, a film and media studies major from Rochester, is a member of a summer street team organized by the GRFH and staffed by fellow Rochester students. They attend community festivals and other events to talk with parents about ways to eat healthily and stay active. In September, they invited parents from the neighborhood to Douglass House to share healthy food and recipes. These are “baby steps,” Elim says, but they have an impact. A sugar chart, showing the number of teaspoons of sugar in popular sweetened drinks, is something “that really shocks parents.”

But education can go only so far.

“We don’t have an obesity problem because people think ice cream is good for you,” Aligne says.

ON THE MOVE: Eyshawn Mason of Rochester takes part in an autumn Cyclopedia ride. Pediatric residents started the program, using bicycling as a way to help keep kids healthy and connect them with their community. (Photo: Adam Fenster)

ON THE MOVE: Eyshawn Mason of Rochester takes part in an autumn Cyclopedia ride. Pediatric residents started the program, using bicycling as a way to help keep kids healthy and connect them with their community. (Photo: Adam Fenster)Wade Norwood ’85, director of community engagement for the Finger Lakes Health Systems Agency, says, “Society has changed. Opportunities not to be active have proliferated. We’ve developed incredible reliance on convenience foods. Our food supply system makes unhealthy foods more accessible, and healthy ones less. We need to make it easy and more natural to do the healthy thing.”

And because those trends have been created at the societal level, policy change is an important part of the equation in curbing problems of weight. Norwood helps to direct the agency’s Healthi Kids Initiative, a community-based coalition advocating for policy and practice changes to help kids maintain a healthy weight. Among its goals are establishing better standards for food at schools and childcare centers, policies to support breastfeeding, safer and more accessible play areas, and at least 45 minutes of in-school activity.

“For students in the city school district, in particular, elementary school recess had been eroded because of pressures for students to maximize the time they spend preparing for standardized exams,” says Norwood. “Only one elementary school in three was allowing for daily recess.”

Armed with research demonstrating the importance to children’s health of school time for physical activity—and its academic benefits in enhancing children’s ability to concentrate in the classroom—coalition members convinced parents, teachers, and school leaders to restore daily recess last spring in a group of city elementary schools. The recess requirement was adopted district-wide last year.

And in response to findings that play happens not just in parks and playgrounds, but also in spaces all over neighborhoods, the city government created a program, Rec on the Move, to fund and staff a van that travels through city neighborhoods to teach children fun ways to be physically active and provide play equipment. The program was so well received that the GRHF has funded a second van to help promote more outdoor play.

“It’s multimodal,” says DeVinney. “We’ve got to come at it in schools, in childcare centers, and in the community, with policies and practices that create healthy options as the default.”

While the problem of obesity is affecting all sectors of American society, the numbers are worst where incomes are lowest. “It’s not about your genetic code—it’s about your zip code,” says Cook.

That’s for a host of reasons. The cheapest food is often the least healthy and nutritious. Unsafe streets make it hard for children to walk to school or to play outside. And stress—from lack of time, economic worries, and more—lures people to the security of comfort foods or time in front of the television.

(Chart: Steve Boerner)

(Chart: Steve Boerner)The two most pressing challenges to adopting healthier behaviors are time and money, says Norwood.

In Rochester’s Beechwood neighborhood, though, community members are taking control to improve their health. Grocery stores are a cab or bus ride away from the neighborhood, and residents have been largely reliant on the snack foods available at the ubiquitous corner stores that fill urban neighborhoods.

“It’s not so much that we have a food desert—we have a food swamp,” says George Moses, director of the community group North East Area Development (NEAD). “There’s plenty of food, but it’s not real food.”

So last November, NEAD bought one of the stores with funding from the GRHF, turning it into the Freedom Market, a headquarters for healthy food and a safe neighborhood gathering place.

Salty, fatty snack foods are being phased out, replaced with nuts, seeds, fruits, and vegetables.

Joanne Larson, the Michael W. Scandling Professor of Education at the Warner School, says, “The residents wanted to have the ingredients that would go into a traditional Sunday dinner in the African-American community, so we’re offering fresh greens of all kinds, potatoes, onions, corn, grapes, plums, squashes, lettuce, and so on. And on Saturdays in the summer we have a farm stand right outside the store, which almost sells out every Saturday.” Along with colleague Joyce Duckles, clinical assistant professor in the Warner School, and several graduate students, Larson has been working with NEAD to perform a qualitative assessment of the project, helping to track the changes and interviewing residents, customers, and store employees—called the “Food Corps,” they’re all neighborhood residents with children up to 10 years old.

The Freedom Market is a success, with plans afoot to begin offering healthy prepared meals. “We’re finding that it’s not necessarily a matter of education about obesity or healthy food—it’s access,” Larson says. “People come in six or eight times a day. They use it like their fridge, so what’s offered in the stores is going to matter a lot, in terms of addressing the obesity problem.”

Moses says the store is an example of “holistic community development. Nothing is by itself—and no one thing is going to take care of everything.” But he, like Larson, sees cause for pride and optimism in what has happened already at the store.

“The community is in collaboration with the University in solving the problem together. We’re constantly collecting data, and using it,” says Moses, who sits on the committees of both HEART and Healthi Kids. The groups work together, sharing data and strategies. Ultimately, NEAD hopes to expand its effort to include other corner stores across the city and develop a model that could be adopted in other urban areas.

People involved in combating obesity often compare it to the fight against tobacco that began to be waged a generation ago. It’s different in some ways—“No one has to smoke, but we all have to eat,” DeVinney observes—but similar in others.

“What worked for tobacco were taxes, laws restricting the environment where it was OK to smoke—especially to protect children. And the public messaging wasn’t just informational. It was counter advertising” that doesn’t just explain to people the hazards of smoking but hits them at an emotional level, says Aligne.

To turn the tide on obesity, as with smoking, “it’s going to take a social movement. And persistence,” Cook says.

“This didn’t happen overnight, and it’s not going to be solved overnight,” says Bennett of an effort that she and others predict will span decades. “There’s no quick fix for this.”

For Cook, it comes down to a matter of social responsibility.

“Children have zero voting power. We have to do what’s right for them.”