Curatorial Statement for Seven Videos:

The Metaphor of “Flying and Falling” in Contemporary East Asia and Visual Arts

All of a sudden, I feel an itch under my arms. Aha! The itching is a trace of where my artificial wings once sprouted. Wings that are missing today: pages from which my hopes and ambition were erased flashed in my mind like a flipped-through dictionary. I want to halt the steps and shout out for once:

“Wings! Grow again!”

“Let’s fly! Let’s fly! Let’s fly! Let’s fly just one more time.”His eyes are staring, his mouth is open, his wings are spread. This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet. The angel would like to stay, awaken the dead, and make whole what has been smashed. But a storm is blowing from Paradise; it has got caught in his wings with such violence that the angel can no longer close them. This storm irresistibly propels him into the future to which his back is turned, while the pile of debris before him grows skyward. This storm is what we call progress.

At 3:00 p.m. on Wednesday the 18th of February, 1931, I will take off from Mercy and fly away on my own wings. Please forgive me. I loved you all.

[signed] Robert Smith,

Ins. agent

Figure 1. The inventors of Cai Guo-Qiang: Peasant Da Vincis,

Figure 1. The inventors of Cai Guo-Qiang: Peasant Da Vincis,

Rockbund Art Museum, Shanghai, 2010.

Photo by Lin Yi, courtesy of Cai Studio.

Earlier this year, Cai Guo-Qiang, the Chinese-born artist who is by now globally known for his orchestration of the 2008 Beijing Olympics’ majestic and spectacular fireworks, curated an exhibition titled “Peasant da Vincis” (nongmin dafenqi) at the newly inaugurated Rockbund Art Museum (RAM) in Shanghai. The original building for the RAM was built in the 1930s as one of the first modern art museums in China. Located amid the Bund (waitan) where dozens of large-scale neoclassical buildings line along the Huangpu river, the building is a part of the legacy, and the evidence, of the city’s early 20th century heyday. In this historical site, which now features a redesigned interior as a contemporary art gallery, Cai unravels his story about temporality and subjectivity in contemporary China. Cai’s curatorial project resulted from his years-long collecting of flying saucers, air planes, submarines, and other curious gadgets invented by more than fifty peasants from all regions of China, hence the exhibition title named after Leonardo da Vinci, the 15th century Italian artist and Renaissance man who also wished to fly. One of the works featured in the exhibition is titled Fairytale, for which dozens of apparatuses suspended in the air fill the vertical space of the three-story high atrium, with live birds flying freely and chirping rhythmically in between the makeshift gadgets. This monumental display of individual creativity, fantasy, and romantic dreams opposes the Pudong district’s cityscape just across the river. In Pudong, the techno-centric post-industrial future that has yet to exist is reified as an image, as evidenced in a cluster of skyscrapers. This particular logic laden in Pudong is not dissimilar to that in the 2010 Shanghai World Expo, which was held concurrently with Cai’s exhibition, and in which national and commercial pavilions represent the desire for a better future, rather than the future itself. Situated amid the city’s bygone glory of the early 20th century while safely distanced from the neoliberal-postmodern future across the river, Cai’s exhibition pays affective homage to the Chinese subalterns transported from the more recent, socialist past of the People’s Republic of China, and in so doing disrupts the strong sense of linear temporality that the city has imposed on a spatial scale.

Figure 2. Cai Guo-Qiang, installation view of Fairytale, Shanghai, 2010.

Figure 2. Cai Guo-Qiang, installation view of Fairytale, Shanghai, 2010.

Photo by Lin Yi, courtesy of Cai Studio.

My curatorial statement to the seven video art works screened during the conference “Spectacle East Asia: Translocation, Publicity, and Counterpublics,” held in spring 2009 at the University of Rochester, begins with Cai’s artistic project because “Peasant da Vincis,” like the video art works, calls for a closer examination of a certain temporality and historicism in place in today’s East Asia. Another element that connects Cai’s exhibition to the art works is the artists’ strenuous effort to explore subjectivity expressed via such issues as the public, ethnic minority, renmin (the people) or nongmin (the peasant) in socialist China, minjung (the people) in 1980s Korea, etc. This effort, it should be noted, reveals the limitations of these existing paradigms by addressing new ways of imagining sociality and agency. Though my essay will trace how these art works elucidate questions around temporality and subjectivity, no single theme or characteristic of “Asianness” links them all together. What might be “Asian” about the art works is that they, with varying degrees, step outside the rapidly calcifying standard narrativizing impulse of current discourse on the visual arts and cultures in, from, and of contemporary East Asia.

Preserving the past as heritage and imagining the future as it ought to be, post-socialist China seems to pursue a state-planned, immensely androcentric process of technology-driven modernization and urban development at an unprecedented pace and scale, all under the banner of the socialist market economy. This future-oriented trajectory in China in particular, and in East Asia more generally, is not only manifest in urban transformation but also practiced more broadly in the discourse of culture and the visual arts. The narrativization of the relatively nascent scholarly field of contemporary East Asian arts and visual cultures is dominated by the acts of chasing after annual reports from auction houses and of counting the number of newly established film festivals, art biennales, and other touristic, cultural sites in key cities like Beijing, Seoul, Shanghai, and so on. This stagist, development-oriented temporality embedded in the discursive and institutional formation of discourse reinscribes the existing cultural and geographical hierarchies: the sophistication of the field and the diversity of objects of study in these emerging centers are deemed to be rapidly catching up with, but not yet quite parallel to, those of other, Western centers such as New York, London, and Berlin. The current discourse on visual cultures of contemporary East Asia, albeit celebratory in its tone, is therefore one that is fraught with limitations.

One way of countering these limitations is unraveling the intricacy and density in artistic languages with which artists visualize the very undercurrents of each locale in transition. Curator and critic Okwui Enwezor, for example, has been invested in mapping the aesthetic relations among these locales, with the understanding that in developing economies and democratizing societies different imaginations for political subjectivities emerge together with a range of aesthetic languages.[1The danger in privileging these transitional locales is that other locales that are more or less stabilized may seem left out of what is perceived as a vibrant cultural scene. The impulse to historicize Japan that the conference participants felt during the “Spectacle East Asia” presentations and discussions in Rochester can be one possible example of counterproductivity.] His project with the 2008 Gwangju Biennale in South Korea is closely aligned with the larger vein of his work, in which he actively seeks a reconceptualization of visual cultures arising from regions and areas that are widely considered postcolonial.[2See, for example: Okwui Enwezor, “Mega-Exhibitions and the Antinomies of a Transnational Global Form,” in Documents 23 (Spring 2004).] In more recent projects, curators such as Enwezor and Nicolas Bourriaud have suggested geographical and temporal multiplicities in modernity via concepts like “offshore” and “off-center.”[3Nicolas Bourriaud (ed.), Altermodern: Tate Triennial (London: Tate Publishing, 2009); and Okwui Enwezor, “Modernity and Postcolonial Ambivalence,” in the same issue. See also: Enwezor’s “The Politics of Spectacle: The Gwangju Biennale and the Asian Century,” republished in this issue, and originally from The 7th Gwangju Biennale: Annual Report, ed. Okwui Enwezor (Gwangju: Gwangju Biennale, 2008).] Through the lens of re-defining modernity, the temporal linearity established between, say, Paris and Shanghai can be challenged, or at least newly understood, as multiple “habitations of modernity” (a term that Enwezor borrows from postcolonial Marxist historian Dipesh Chakrabarty) become the very sites of heterotemporality. And these are the sites where the vexed relationship between aesthetics and subjectivity is rearticulated or even contested. This intellectual conceptualization of multidirectional, heterochronical modernities is highly significant if we are to re-think the “belated entry” of Asia into studies of contemporary visual arts in a way that is not solely dependent on neoliberal expansion into the market and production sites.

As art historian Miwon Kwon recently stated in the journal October’s Questionnaire on “the Contemporary,” the rigidification and categorization of the field of art history can be shaken up by an emerging “subfield” like contemporary Chinese art, which does not comfortably fit into the conventional parameters of contemporary art history (historically defined as having no geographic marker except for that of Western Europe and North America) or Chinese art history (which is considered pre-modern).[4Miwon Kwon, untitled statement, in October 130 (Fall 2009), 13-15.] Not as a mere addition to the existing paradigm but as a driving force for change, East Asia’s entry into the discourse has the potential to cause a fundamental epistemological shift in our ways of thinking about modern and contemporary visual arts and cultures. In order for this to happen, the complexity of the aesthetic languages that have always already existed in the works of visual arts and cultures themselves need to be discussed and critiqued in equally rigorous theoretical frameworks, as the essays by Caitlin Bruce, Rika Iezumi Hiro, and Hyejong Yoo have showcased in this issue.

My way of imagining a range of possibilities for contemporary East Asia and its artistic production is bookended by analyses of Cai’s exhibition “Peasant da Vincis,” an artistic project that I consider to be a representation of flying and falling, and which can be also commonly found in the allegories of paradoxical subjects: the narrator in the Korean colonial writer Yi Sang’s Wings;[5Yi Sang, Wings (1936), trans. Walter K. Lew and Youngju Ryu, Modern Korean Fiction: An Anthology, eds. Bruce Fulton and Yong-min Kwon (New York: Columbia University Press, 2005), 83-4.] Paul Klee’s Angelus Novus, as read by Walter Benjamin, the Jewish intellectual who was living as a stateless citizen in Paris, hiding from the Nazi regime in Germany when he wrote his “Theses on the Philosophy of History”;[6Walter Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” in Illuminations, ed. Hannah Arendt, trans. Harry Zohn (New York: Schocken), 257-8. Original version in German completed in Spring 1940, first published in Neue Rundschau 61:3 (1950).] and Mr. Robert Smith, a suicidal black character selling life insurance door-to-door during the Great Depression from Toni Morrison’s novel Song of Solomon.[7Toni Morrison, Song of Solomon (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1977), 3.] These are the moments where heterotemporality has produced hopes and aspirations of transitional times and the violence therein. On the very sites where all of past and present, colonialism and postcoloniality, emancipation and repression, and fascism and liberation exist together as potentialities, transitional times can never end because they are infinitely stretched. Or, flying high can meet a sudden fall, with no time for either transition (to a landing platform) or rescue (from a fatal wound). On these sites of intersection, convergence, and uncertainty, how do art works then visualize the glimpse of hope in face of the endless deferral for a utopia and the threat of instant collapse?

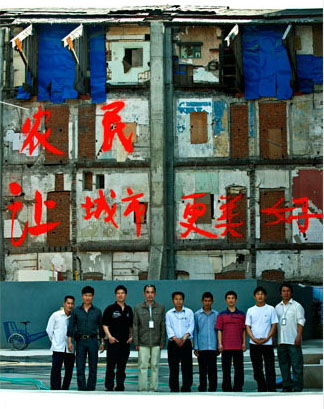

Through the inopportune presence of rural peasants in Shanghai’s urbanity, Cai’s exhibition metaphorically interferes with the seemingly invincible linearity of the temporality deeply rooted in today’s Chinese society (what Dipesh Chakrabarty calls “secular, disenchanted, continuous time”).[8Dipesh Chakrabarty, Provincializing Europe: Post-colonial Thought and Historical Difference (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2000).] The viewers entering into the RAM complex are welcomed by slogans painted in red Chinese calligraphic style, reminiscent of propaganda banners that until recently decorated factory walls and farming areas across China. Among them is: “Peasants—Making a Better City, a Better Life” (nongmin rang chengshi geng meihao), a spin on the Shanghai Expo’s slogan of “Better City, Better Life” (chengshi, rang shenghua geng meihao).

Figure 3. Inventors in front of

Figure 3. Inventors in front of

Peasants—Making a Better City, a Better Life, Shanghai, 2010.

Photo by Lin Yi, courtesy of Cai Studio.

How can peasants be seen as part of the Expo-generated spectacle of modernization, except through a merely rhetorical repetition of peasants as the true owners of the Republic or through peasants-turned-migrant workers from provincial towns mobilized as manual labor in the construction of the Expo’s world village, or its service industry?

Figure 4. Cai Guo-Qiang, installation view of Wu Yulu’s Robot Factory, Shanghai, 2010.

Figure 4. Cai Guo-Qiang, installation view of Wu Yulu’s Robot Factory, Shanghai, 2010.

Photo by Lin Yi, courtesy Cai of Studio.

On the one hand, Cai’s exhibition takes a pleasant look at small, entertainment-driven, participatory inventions, along with handcrafted, human-sized metal robots imitating Western masters such as Jackson Pollock, Damien Hirst, and Yves Klein. For instance, a pre-programmed Pollock robot reenacts the “dripping” of acrylic paints on mass-produced canvases, as if to mock Harold Rosenberg’s investment in the artist’s unique expressions. The exhibition can be seen as arguably more entertaining than the Expo itself, as if aptly demonstrating the utopian investment of the Cultural Revolution—the peasants can do it too, perhaps even better. The wildest imaginations and dreams (mengxiang) of individuals seem to be the theme, and inventiveness and creativity go hand in hand with the product designs with which the World Exposition format has been so closely intertwined since its inception in 19th century Europe.

Figure 5. Cai Guo-Qiang, Monument, Shanghai, 2010. Photo by Lin Yi, courtesy of Cai Studio.

Figure 5. Cai Guo-Qiang, Monument, Shanghai, 2010. Photo by Lin Yi, courtesy of Cai Studio.

Despite the somewhat benign emphasis on peasants’ creativity, the presence of rural peasants in 21st century cosmopolitan Shanghai seems out of place and out of sync, as peasants have the historical connotation of Chinese subalterns with whom enlightened workers will march into socialist revolution in China and the world. The figure of the Chinese peasant can thus be nostalgic, in the sense of Rey Chow’s definition of nostalgia as not “an attempt to return to the past,” but “an effect of temporal dislocation” and “something having been dislocated in time.”[9Rey Chow, “A Souvenir of Love,” in Ethics after Idealism (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1998), 147.] Instead of considering the peasants as backward, thereby comfortably putting them within a stagist understanding of modernity, we can consider them as figures of non-synchronism, or those that resist synchronization, like ghosts who return from the limits of time and haunt the present.[10Bliss Chua Lim, “Spectral Times: The Ghost Film as Historical Allegory,” in positions: east asia cultures critique 9:2 (Fall 2001), 287-329.] The first and only work exhibited on the ground floor—which thus cannot be avoided or skipped by visitors—is a composite of three objects: a picture of Tan Chengnian, a peasant inventor from Shandong province who died in 2007 from injuries sustained during a trial flight of his homemade airplane; the engine of the very wrecked plane from that 2007 accident; and an epigone-like text that narrates his tragic story. This narrative of a man who lived and died for his dream warms our hearts affectively, bringing us into the realm of sentimentality and the romance of daily lived experience, and away from the rationality-driven state development plans, of which the Expo is a part. Before the homage paid to the ghost of Tan Chengnian, we too become nostalgic figures, out of place and out of sync in today’s Shanghai.

In the case of South Korea, the uncanny ghostly figures who break the ostensible homogeneity of time by returning to the present are not peasants but migrant workers from other developing countries in Asia such as Nepal, Indonesia, and Vietnam. It can be argued that when a South Korean citizen encounters the sites of the labor rights protests of “dark-skinned” workers, she or he may recall the minjung labor movement of the 1970s and 1980s that ultimately achieved the initial step toward the nation’s democratization by making possible the first democratically-held presidential election.[11Hagen Koo “Engendering Civil Society: The Role of the Labor Movement,” in Korean Society: Civil Society, Democracy and the State, ed. Charles Armstrong (New York: Routledge, 2002), 109-131; and Yong Min Moon, “The Illegal Lives: Art within a Community of Others,” in Rethinking Marxism 23:1 (July 2009), 403-419.] Although Korean workers have lost the political leverage needed to incite large-scale social change, their legacy has nonetheless been inherited by migrant workers. During their own struggles, the migrants have appropriated the symbols and references of the minjung labor movement. There is a dramatic irony in this, however: the term minjung, roughly translated to English as “people,” encompasses political subjects who are projected to rise above authoritarian regimes and colonial oppression, and minjung has always been conceptualized as ethnically Korean, thus precluding the foreign migrant workers from this historical categorization.

But what if today’s subalterns in South Korea are these very workers who are at the bottom of the socioeconomic order, fighting against the utter denial of their basic rights amid a constant threat of deportation? What role does their presence play in questioning South Korea’s collective past of social revolution and its representation of a national community? Several projects by Mixrice, a collective composed of native Korean artists and transnational migrant workers, vehemently deny sympathy-generating mass media representations of the workers. In other projects, Mixrice challenges the closed identity and collective memory of the Korean nation-state, and moreover questions the possibility of forming a stable identity at all. Conversation 03 is edited from audiovisual documentation of a Nepali community theater group’s rehearsal for a performance entitled Illegal Life. During a practice performance, the Nepali director insists on a better translation of “emotion into action,” and the exploitation and eventual death of a worker sans papiers is repeated, honed in on, and later applauded by other worker-viewers at the site. The camera zooms in to closely capture a worker-cum-actor who, with a sense of confidence in acting, demonstrates to his colleague how to express pain and “die” on stage. The editing is done carefully to draw the viewers’ attention to the repeated nature of practice for a better enactment of “real” agony that the workers experience in Korea. In highlighting the apparatus of fiction with which this verisimilar story is constructed, Conversation 03 questions the politics involved in the formation and representation of community, be it an ethnic majority or a minority in a given society.

A collective past in the form of unrecognizable fragments also returns to the present in Hangzhou-based artist Gao Shiqiang’s Great Bridge. A black-and-white rendition of two middle-aged male characters living in substantially different socioeconomic situations is dubbed with repeated female ghost whispers of “daqiao (great bridge).” Daqiao in this case refers to the nationalistic project of constructing the world’s largest bridge in Hangzhou during the 1950s state-sanctioned economic plan. While Gao does not show any visual image of the bridge, he employs sound as the primary symbol of the socialist past for people living in the current moment. The outdated socialist agenda that was executed in the name of the people cannot simply be denied or put into the past, as it has an undeniable physical and material effect on the diverse bodies that occupy the here and now. Great Bridge seems to insist on the necessity of resurrecting past wrongdoings, even though the whirlwind in the name of progress takes the “angel of history” off the ground and into the future. What other subjectivities are imagined in artistic practices which, like Benjamin’s angel, counter the homogeneous, empty subject?

Touching upon the issue of collective subjectivity, artist Zheng Bo begins a participatory art project Karibu Island with a video that asks those taking part to envision a place where time flows backward. After watching audiovisual material composed of rewound movie clips—men and women running backwards, and Siddhartha returning to Maya’s womb—the participants are invited to the Karibu Islands. There, the participants are born as fully-grown adults and eventually become babies. A group exercise of making birth certificates brings forth such questions as profession, assets, family relationships, nationality, gender, and sexuality: How many kids would I have when I am born, at, say, age eighty five?; What kind of profession would I have?; Where would I be born? During the three consecutive workshops for gay, lesbian, and “straight” groups held at the Beijing Queer Community Center in 2007, this activity provided the participants with an unreal space within which they could discuss various possibilities of policy-making and social transformations. The division between here and there is created by a distorted temporality that the artist sets up, while the constant oscillation between fantasy (What kind of person would my partner be at the time of my birth in the Karibu Islands?) and the practicality of achieving this fantasy in reality (If I want to have this type of partner in the future in Beijing, what steps would I go through to meet her and make a living with her?) brings the future into the past tense and vice versa. This oscillation results in bringing the participants back to the visceral reality of the present and calls for potential changes to be made as they are envisaged, verbalized, and hoped for during the workshops.[12The Karibu Islands project can be considered as what cultural critic Grant H. Kester would call “the facilitation of dialogue among diverse communities” and “the creative orchestration of collaborative encounters and conversations, well beyond the institutional confines of the gallery or museum.” Borrowing British artist Peter Dunn’s words, Kester then defines these artists as providers of “cultural context rather than cultural content.” In his attempt to develop models of such artistic activities that derive from conversations, Kester theorizes what he calls “dialogical aesthetics,” which induces the linkage between “new forms of intersubjective experience with social or political activism.” Kester, Conversation Pieces: Community + Communication in Modern Art (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004), 1-9.]

Although the artist emphasizes the dialogical aesthetics of building a new community, I want to highlight the spatial dimension of the Karibu Islands. As if to reflect the kinds of “other spaces” that Michel Foucault conceptualized as heterotopias—“counter-sites, a kind of effectively enacted utopia in which the real sites, all the other real sites that can be found within the culture, are simultaneously represented, contested, and inverted”—the Karibu Islands exist in a particular, physically-existing site: a not-for-profit organization’s office housed in a high-rise apartment building in the financial district of Beijing.[13Michel Foucault, “Of Other Spaces,” trans. Jay Miskowiec, Diacritics 16 (Spring 1986), 24. Originally written for a lecture given by Foucault in 1967, the text was first published in French in Architecture-Mouvement-Continuité in October, 1984.] Contingent on a real space, Zheng’s Karibu Islands project creates a specific public and a specific public space, challenging the larger societal insistence on a homogenous time, space, and subjectivity especially prevalent in the most rapidly developing capitalist regions.[14Heterotopias, according to Foucault, have a function in relation to all the space that remains: “Either their role is to create a space of illusion that exposes every real space, all the sites inside of which human life is partitioned, as still more illusory. . . . Or else, on the contrary, their role is to create space that is other, another real space, as perfect, as meticulous, as well arranged as ours is messy, ill constructed, and jumbled. The latter type would be the heterotopias, not of illusion, but of compensation.” Foucault, “Of Other Spaces,” 27. For more discussion of Karibu Islands, please see the artist’s own writing in which he situates his own practice within a critical dialogue on socially engaged art in mainland China. Zheng Bo, “Creating Publicness: From the Stars Event to Recent Socially Engaged Art” in Yishu: Journal of Contemporary Chinese Art 9:5 (September/October 2010), 71-85.] If the project’s dialogical aesthetics results in an inquiry into subjectivity, the video opens up the participants to imagine (or fly to) an “other space,” an effective utopia.

In his Self-portrait 78, Kwak Duck-jun constructs a space whereby a complex play with mediums such as a glass pane and a camera results in the processes of dis-identification and re-identification, all the while revealing the social and cultural heterogeneity of the space that a subject occupies. A Zainichi Korean, born in Kyoto, Kwak began the large-scale photography series Presidents and Kwak in the early 1970s. He photographs a scene in which he superimposes a mirror (a quintessential heterotopia for Foucault) onto the bottom half of an American president’s face (that of Ford, Carter, Reagan, and so on), as published on every Time magazine’s cover that celebrates the winner of a presidential election, reflecting his own face in the mirror and thus montaging his minority self with that of the “world face.”[15The artist denies allegations of anti-Americanism. See: Tatehara Akira “Kwak Duck-jun: The Artist’s Journey,” in Kwak Duck-jun: 1960s-1990s (Seoul: Donga Gallery, 1997). Originally published in Japanese and Korean; the text in Korean is also available on the National Museum of Contemporary Art, Korea’s website: http://www.moca.go.kr/item... (last accessed July 2010).] On the surface of Kwak’s photograph, not only the subjects depicted but also the sites of representation are juxtaposed as disparate entities.[16It should be noted that the photograph includes not only the two-dimensional montaged surface but also the act of representation: we can see a glimpse of Kwak holding the mirror while looking straight at it, with the camera located behind his shoulder. Two visual effects take place in this case. First, the fragment of Kwak’s body turning back on the viewers makes it clear that Kwak is highly aware of the coordinates of his own position vis-à-vis historical and spatial heterogeneity (i.e. the self who is aware of where it stands in the heterogeneous world). Secondly, the process of dis-identification with the self occurs in the doubling of Kwak’s image, which is related to the first effect in that this splitting disallows stability and permanence in self-assertion and promotes a constant awareness of one’s shifting historical and social position.] The Presidents and Kwak series, demonstrating the importance of mediation and representational tactics to Kwak’s work along with his reiteration of the self as an “other” in Japanese society and the world, shares similarities with his performative video Self-portrait 78. Othering of the self takes place in the shooting process of Self-portrait 78 through the use of a glass pane that functions like the mirror that Kwak holds for Presidents and Kwak. Shot at a frontal angle, the video consists of Kwak pressing his face up against a broken pane of glass while a monitor, standing before the glass pane, live streams his performance. In this closed feedback loop, Kwak is able to glare at the image of himself featured on the monitor screen while the glass pane reflects Kwak’s projected image on the monitor. Although it may seem like a mise-en-abyme, this set-up is not an effort to create a gesture of endless reference. While the glass-cum-mirror distances Kwak from his self-representation, facilitating the process of dis-identification, Kwak’s rubbing of his face against the cracks in the glass and licking them with his tongue provokes the viewers’ physical discomfort, as if we were standing in person before him. Indeed, the viewers, whose position is that of the camera, are those who stare at Kwak and to whom Kwak returns his gaze. Through a series of mediations, our sense of proximity to Kwak is enhanced even to the point of assisting us, however imaginatively, in taking the place of Kwak who stands before the “mirror” and who carefully observes the distorted self-portrait over there in the “mirror.” Watching the video, the viewers also become highly aware of their own socio-cultural positions, as Kwak, through his uncomplicated emphasis on the materiality of his body, strives to deliver his own cultural status to the viewers.[17In terms of formal language, Kwak’s video work can be discussed within the context of previous artistic experiments with the portable video camera and with instant video feedback during the 1960s and 1970s, as explored by Rika Iezumi Hiro in her contribution in this issue, or by other scholars on such works as Andy Warhol’s experimental films and Dan Graham’s video installations in mirrored rooms. My reading of Kwak’s work, however, tries to remain faithful to the feeling of discomfort delivered by Kwak’s blatantly sado-masochistic emphasis on his bodily presence—a self-portrait that confronts the viewer head-on.]

The metaphors of being beside an other, or the efforts to form an ethical relation with others who occupy divergent sociopolitical positions, are also provocative in the aesthetic language of both Chen Chieh-jen and Lim Minouk. For Portraits of Homeless People, Renters and Mortgagers, Chen constructs a film set with wooden molds recycled from construction fields. In the spectacular yet melancholic vision of a modern city’s ruins, Chen films his friends stepping over the molds on the floor to arrive at the center stage on which rises a cement model of an apartment building. On his work, Chen comments: “All of my friends in the film, except for one who is homeless, have to work to pay their high rent or mortgage just like most people in the city. Although they live in these homes, they don’t really own the spaces. This kind of depressed [and] anxious situation where people have to endlessly work for their living space and worry about losing their jobs is what I wish to depict in this film.”[18Artist’s statement sent to the author by the artist.] Although the subjects’ identities are not explicitly stated within the video’s narrative, their collective agony has infiltrated the audiovisual elements of the video, as in the case of the sound of a propeller mixed in with slowly pulsating monotone electronic notes. In its structure, the video is segmented into individual portraits or sometimes double portraits: the opening scene captures an empty set; the subjects appear from the left or right front of the screen and start walking toward the center stage, where they pause for a moment; the screen then fades into dark before it returns to the opening scene of an empty urban landscape; and another subject enters into the screen to repeat the journey to the center. In a gallery setting, Chen wants the video to be screened continuously in order to enhance the sense of repetition, thereby achieving a collective portrait in the sense of a chain of separate portraits that are metaphorically equated within the setting that they inhabit—a modern city in the aftermath of extensive urbanization, devoid of warmth, care, and affection of inhabitants for one another.[19Here I am making a loose reference to the idea of “a chain of equivalence” conceptualized by Chantal Mouffe and Ernesto Laclau. See: Mouffe and Laclau, Hegemony and Socialist Strategy (New York: Verso, 1985), xviii.]

Lim’s subjects of ethical equation in her video Game of Twenty Questions are the artist’s own daughter and the participants in the Seoul municipal government-sponsored 2007 Multicultural Festival.[20The festival is the fourth incarnation of an annual event organized by the city of Seoul, with its official name changing from “The Foreign Workers Festival” to “Migrant Workers Festival,” and to “Multicultural Festival” in 2007. This change reflects the shift in the government’s cultural policy towards migrant workers. And it also attests to the increasing rate of interracial marriage that is forcing both the central and municipal governments to make policy decisions on the country’s unanticipated multiculturalism.] Interested in modernization and industrialization in South Korea, Lim probes the social phenomenon of the country’s rapidly increasing multiracial population, which includes her own daughter, born to a Korean mother and a French father. Lim is acutely aware of the Korean racial hierarchy according to which a Korean interracial child with a Caucasian parent stands higher than “dark-skinned” migrant workers’ children. In Lim’s split-channel video, these latter, ethnically “other” children are frequently shown singularly on the left screen, juxtaposed with Lim’s daughter who is featured on the right screen. The structure of a split screen has a visual function that is different from the other mediating tools used by Kwak (the glass pane, camera, and mirror) or Chen (a theatrical setting and ambient sound), which put their emphases on identification: the immeasurably tiny, seemingly insignificant gap between the two screens—just a thin line, in fact—symbolizes the insurmountable gulf between the subjects portrayed on the two sides. Within this visual structure, the image of Lim’s daughter, a surrogate of Lim herself, on one side meets images of other loners (migrant workers, their children, a guinea pig, and balloons, often featured individually) on the other side. Single balloons strangely rolling on the ground of the Multicultural Festival site, usually shot from afar, sporadically appear on screen from the beginning. Lim only reveals the origin of the balloons towards the video’s end, with a shot of hundreds of multicolor balloons being released into the sky to signal the beginning of the festival. With her daughter’s image as an entry point to the world of fallen balloons—an allegory of the resistance to and critique of the naïve optimism embedded in Korean-style multiculturalism—Lim expresses a sense of crisis, one that gains a heightened urgency for viewers since the fate of these balloons is presented in a reversed temporal sequence.

Like the balloons in Lim’s work, the kites and paper gliders in Sangdon Kim’s Discoplan also take off the ground only to fall right back to it. The driving force in Discoplan is the artist’s continual dream of an alternative world, despite his recognition of inefficacy and futility in his attempt to intervene into social reality. In the name of a community outreach and participatory art workshop, Kim opens up a dialogue among his artist friends and residents of Dongducheon, a small city located midway between Seoul and the Demilitarized Zone. Due to its surrounding mountains (which are geographically advantageous for military purposes), the region had been a base for the Japanese imperial army during the Japanese colonialization of Korea in the earlier part of the 20th century, which was succeeded by the U.S. army base in the latter half of the century. The specific site captured in Discoplan is near Dongducheon’s Camp Nimble, the ownership of which has recently been transferred from the U.S. military to the Korean Ministry of Defense, only to be re-sold to real estate developers. After the shift in ownership, it was discovered that the site cannot be used due to serious soil contamination and thus public access to it has been denied. When Kim looked at the helicopters flying over the barbed wire fence around the site, he was inspired to invite residents to build flying gadgets with the mission of transporting flower seeds over the fence—an emblematic act of resisting the military imperialism that is now coupled with neoliberal logic.

Kim heavily edits the documentary footage taken during this activity in order to help viewers witness the participants’ incessant efforts to overcome the physical and symbolic barrier, and moreover to let viewers discover humor in the resistant gap between the participants’ agenda and their actions. The former goal—the political and environmental regeneration of the century-old military base identified with colonialism and imperialism—is grandiose to say the least; yet, the latter seems trivial and tedious, ranging from filling emptied egg shells with seeds to throwing them over the fence (and ultimately failing at it). Watching their flying gadgets fall back at them because of the reverse wind (the literal manifestation of casting stones against the wind), the participants themselves burst into laughter. Amid their enjoyment and sheer fun in the activity, they laugh. Due to the absurdity and futility of their actions, they laugh again and we the viewers laugh too. The shots are fast-cut to interlink the visuals with the sound effects of exclamatory voices (e.g. “oh!,” “wow,” “argh!,” “oh, no!”) and other sounds (e.g. “whack,” “bam”), enhancing the entertainment value of the video. During the minjung period in Korea, artists attempted to situate art at the core of the social movement, but the art often delivered uncomplicated, two-dimensional representations of present-day dystopias and a coming utopia. Kim’s video is an example of what might be considered a “post-minjung” aesthetics that demonstrates in the most candid way the excruciating longing for change expressed through the performance of translating utopian dreams into tangible tactics, even in the case where these tactics are proven ineffective towards the end goal of a societal-level revolution.

Revolution, dreamed by many in various parts of East Asia during the 20th century—is it possible in the 21st century? In South Korea and China, where one of the most blatant manifestations of neoliberalism is executed on the state-corporate level, what kind of utopia is and can be envisioned by artists? Or, in the case of Japan, a country that has repeatedly fallen into economic recessions for the past two decades and that still has not reconciled with its own past as an imperialist colonizer, what form can the returning of “the oppressed” from the repressed past take in artistic practice?[21For Harry Harootunian and Tomiko Yoda, the post-war economic prosperity and military security that Japan was promised by the U.S. came with the price of keeping the imperial dynasty intact and thus of delaying the very social reforms necessary for “[eliminating] prewar fascism and [putting] into place the foundations of a genuine social democratic structure.” In the immediate aftermath of the war, Japan, with American help, absolved the emperor of responsibility for the war, which began Japan’s endless deferral of acknowledging its war crimes. This long lasting post-war paradigm in Japan ended in the 1990s, with the recession that shattered the myth of Japan’s endless economic affluence. Harootunian and Yoda, introduction to the special issue “Millennial Japan: Rethinking the Nation in the Age of Recession,” of The South Atlantic Quarterly 99:4 (Fall 2000), 619-627.] And we have not even begun to discuss the art of North Korea, a country where the regime is constantly susceptible to temporal synchronicity and considered as a towering example of failed socialism. Bearing in mind the combination of complexity and multiplicity in the region of East Asia, I want to end this essay by citing the parallels that I see in the work of Cai Guo-Qiang and Sangdon Kim as a way of disturbing the tradition of national histories while simultaneously emphasizing the very specificities that allow intricate connections between the two artists working in disparate sociopolitical and cultural conditions.

In both Cai and Kim’s work there exists dual moments of social critique and dreaming of a utopia. What is significant is that they both return to a point in history that they critique by reinventing and retranslating the subjectivities necessary for a socialist revolution (in Cai’s work) and for the minjung democracy movement (in Kim’s work). In “Peasant da Vincis,” on the one hand, the notion of peasants as revolutionary subjects in total solidarity is proven false in the highly individualized creativity that drives these peasants. An array of material manifestations of their inventiveness challenges the monolithic, ideological image of suffering peasants depicted in, for example, the Rent Collection Courtyard sculpture commissioned by the Communist Party in 1965.[22As art historian Michael Sullivan recounts, The Rent Collection Courtyard epitomizes the Chinese government’s demand for sculptures as political propaganda. A group of anonymous sculptors collaborated to produce dozens of life-size sculptures in clay plaster to be housed in the courtyard of a former landlord in Sichuan. The contrast between feudal landlords and suffering peasants is rendered in the Soviet-style socialist realist depiction of human figures. Sullivan, The Arts of China, 5th ed. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008), 307-308. Cai Guo-Qiang is in fact the one who re-interprets this historical collection from a contemporary perspective by staging the process of sculpting The Rent Collection Courtyard in 1999 at the Venice Biennale’s Arsenale, and positing it as representation of the “failed promise of socialist China.” See Britta Erickson, “Cai Guo-Qiang Takes the Rent Collection Courtyard from Cultural Revolution Model Sculpture to Winner of the 48th Venice Biennale International Award,” in Chinese Art at the End of the Millennium, ed. John Clark (Hong Kong: New Art Media Limited, 2000), 184–89.] On the other hand, the very utopian construct of a political subject devoid of private ownership and capitalist impulse also exists in these flying gadgets, as none of the participating peasant-artists explicitly tries to make a profit from their “assets” (i.e. technical skills and materials like scrap metal). Various desires, and above all the desire to fly, a symbol of wanting a world alternative to the current one, are projected onto the objects on display.

Figure 6. Sangdon Kim, Discoplan, 2007. Courtesy of the artist.

Figure 6. Sangdon Kim, Discoplan, 2007. Courtesy of the artist.

In Kim’s Discoplan, the direct critique of minjung subjectivity derives from the participants’ “play” in which each individual, not as a group marching together, endeavors to devise a possible means to fly. The participants-cum-characters arrive with divergent agendas, and they each have equally diverse experiences: a local activist in a black suit spews statistical information in a stern manner; a child receives help from her father to shoot a glider; and an elderly resident, after his sobering explanation of the area’s polluted ecology, ends up flying a kite better than others because he had played with one while in refuge during the Korean War (1950-1953). Without the combination of all qualifications that make up minjung—ethnically Korean, working class men—the subjectivity that is in the making at the site of Dongducheon refutes the exclusive nature of minjung identity. As the video is edited from footage taken with four different cameras, Discoplan deters the viewers from establishing a singular perspective or point of identification, merging its critical commentary on minjung with its form. Critiques of minjung aside, it is nonetheless evident that the participants’ struggle springs from a powerful will to fight against inequality and a strong desire for social justice. And this desire is no less—or perhaps, even more—genuine or real than that of minjung protesters during the 1970s and 1980s, making the site that the viewers witness the very site in which a new form of struggle is being actively grasped and conceived.[23Discoplan was produced in collaboration with and exhibited in 2008 in the former Insa Art Space as part of a larger project, “Dongducheon: A Walk to Remember, A Walk to Envision,” which investigated the concepts of the border and neighborhood near the De-Militarized Zone. A small part of the exhibition was shown at the New Museum, New York in 2008 summer. http://www.newmuseum.org/exhibitions/398 (last accessed July 2010).]

While the little success that Kim’s participants have in flying objects over the fence presents a dilemma for the ways in which to continue the struggle for a more just society, the danger in dreaming an alternative world is manifested in Cai’s work as an ever-lasting dilemma—one that is violent, and fraught with fatal tension. The aforementioned three-story high installation of flying gadgets never reveals itself as a whole, as on each floor the viewers perceive a different aspect of the installation. While the viewers climb up a spiral staircase in order to reach the top gallery, which is linked to the rooftop with a clear skyscraper view, their viewing route seems to mimic the bunch of captured birds that fly upward within the three-story high atrium. The dream of flying, or the impulse to fly, in both birds and peasants is translated to viewers during their poetic journey upward. Upon arrival at the rooftop, the viewers are resituated within the larger frame of the urban space, welcomed by a partial view of Shanghai and fresh air; at the same time, Cai’s exhibition, contingent and incomplete on its own, is fully contextualized in the viewers’ vision within the city’s sociopolitical, cultural, and institutional landscapes. Furthermore, the moment of re-connecting with the external world and fresh air at the top of the building prompts the viewers to feel suddenly freer than the captured birds in the gallery. Can we the viewers fly? Or, at the very least, can we learn to fly? But in Cai’s project, we are disjointed and incomplete in ourselves, as we cannot achieve our own dream of flying. To do so on a sunny day in Shanghai, amid the modern buildings and postmodern skyscrapers, means jumping off the roof, ending one’s life. This violent act only would repeat the tragedy of the peasant inventor Tan Chengnian, Mr. Robert Smith in Toni Morrison’s novel, Walter Benjamin, and the first person narrator in Yi Sang’s Wings.

* For the video art works discussed in this statement, please see the link in the right frame. I would like to thank Shota Ogawa and Zheng Bo for their assistance with selecting and bringing the video art works together for the screening, and I extend my thanks to Kyung Hyun Kim, Soo Youn Lee, and Shota Ogawa for providing me with textual and visual materials I needed to write this essay. I am also grateful for editorial comments by Rachel Haidu, Godfre Leung, Genevieve Waller, and Iskandar Zulkarnain.

1 The danger in privileging these transitional locales is that other locales that are more or less stabilized may seem left out of what is perceived as a vibrant cultural scene. The impulse to historicize Japan that the conference participants felt during the “Spectacle East Asia” presentations and discussions in Rochester can be one possible example of counterproductivity.

2 See, for example: Okwui Enwezor, “Mega-Exhibitions and the Antinomies of a Transnational Global Form,” in Documents 23 (Spring 2004).

3 Nicolas Bourriaud (ed.), Altermodern: Tate Triennial (London: Tate Publishing, 2009); and Okwui Enwezor, “Modernity and Postcolonial Ambivalence,” in the same issue. See also: Enwezor’s “The Politics of Spectacle: The Gwangju Biennale and the Asian Century,” republished in this issue, and originally from The 7th Gwangju Biennale: Annual Report, ed. Okwui Enwezor (Gwangju: Gwangju Biennale, 2008).

4 Miwon Kwon, untitled statement, in October 130 (Fall 2009), 13-15.

5 Yi Sang, Wings (1936), trans. Walter K. Lew and Youngju Ryu, Modern Korean Fiction: An Anthology, eds. Bruce Fulton and Yong-min Kwon (New York: Columbia University Press, 2005), 83-4.

6 Walter Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” in Illuminations, ed. Hannah Arendt, trans. Harry Zohn (New York: Schocken), 257-8. Original version in German completed in Spring 1940, first published in Neue Rundschau 61:3 (1950).

7 Toni Morrison, Song of Solomon (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1977), 3.

8 Dipesh Chakrabarty, Provincializing Europe: Post-colonial Thought and Historical Difference (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2000).

9 Rey Chow, “A Souvenir of Love,” in Ethics after Idealism (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1998), 147.

10 Bliss Chua Lim, “Spectral Times: The Ghost Film as Historical Allegory,” in positions: east asia cultures critique 9:2 (Fall 2001), 287-329.

11 Hagen Koo “Engendering Civil Society: The Role of the Labor Movement,” in Korean Society: Civil Society, Democracy and the State, ed. Charles Armstrong (New York: Routledge, 2002), 109-131; and Yong Min Moon, “The Illegal Lives: Art within a Community of Others,” in Rethinking Marxism 23:1 (July 2009), 403-419.

12 The Karibu Islands project can be considered as what cultural critic Grant H. Kester would call “the facilitation of dialogue among diverse communities” and “the creative orchestration of collaborative encounters and conversations, well beyond the institutional confines of the gallery or museum.” Borrowing British artist Peter Dunn’s words, Kester then defines these artists as providers of “cultural context rather than cultural content.” In his attempt to develop models of such artistic activities that derive from conversations, Kester theorizes what he calls “dialogical aesthetics,” which induces the linkage between “new forms of intersubjective experience with social or political activism.” Kester, Conversation Pieces: Community + Communication in Modern Art (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004), 1-9.

13 Michel Foucault, “Of Other Spaces,” trans. Jay Miskowiec, Diacritics 16 (Spring 1986), 24. Originally written for a lecture given by Foucault in 1967, the text was first published in French in Architecture-Mouvement-Continuité in October, 1984.

14 Heterotopias, according to Foucault, have a function in relation to all the space that remains: “Either their role is to create a space of illusion that exposes every real space, all the sites inside of which human life is partitioned, as still more illusory. . . . Or else, on the contrary, their role is to create space that is other, another real space, as perfect, as meticulous, as well arranged as ours is messy, ill constructed, and jumbled. The latter type would be the heterotopias, not of illusion, but of compensation.” Foucault, “Of Other Spaces,” 27. For more discussion of Karibu Islands,please see the artist’s own writing in which he situates his own practice within a critical dialogue on socially engaged art in mainland China. Zheng Bo, “Creating Publicness: From the Stars Event to Recent Socially Engaged Art” in Yishu: Journal of Contemporary Chinese Art 9:5 (September/October 2010), 71-85.

15 The artist denies allegations of anti-Americanism. See: Tatehara Akira “Kwak Duck-jun: The Artist’s Journey,” in Kwak Duck-jun: 1960s-1990s (Seoul: Donga Gallery, 1997). Originally published in Japanese and Korean; the text in Korean is also available on the National Museum of Contemporary Art, Korea’s website: http://www.moca.go.kr/item/... (last accessed July 2010).

16 It should be noted that the photograph includes not only the two-dimensional montaged surface but also the act of representation: we can see a glimpse of Kwak holding the mirror while looking straight at it, with the camera located behind his shoulder. Two visual effects take place in this case. First, the fragment of Kwak’s body turning back on the viewers makes it clear that Kwak is highly aware of the coordinates of his own position vis-à-vis historical and spatial heterogeneity (i.e. the self who is aware of where it stands in the heterogeneous world). Secondly, the process of dis-identification with the self occurs in the doubling of Kwak’s image, which is related to the first effect in that this splitting disallows stability and permanence in self-assertion and promotes a constant awareness of one’s shifting historical and social position.

17 In terms of formal language, Kwak’s video work can be discussed within the context of previous artistic experiments with the portable video camera and with instant video feedback during the 1960s and 1970s, as explored by Rika Iezumi Hiro in her contribution in this issue, or by other scholars on such works as Andy Warhol’s experimental films and Dan Graham’s video installations in mirrored rooms. My reading of Kwak’s work, however, tries to remain faithful to the feeling of discomfort delivered by Kwak’s blatantly sado-masochistic emphasis on his bodily presence—a self-portrait that confronts the viewer head-on.

18 Artist’s statement sent to the author by the artist.

19 Here I am making a loose reference to the idea of “a chain of equivalence” conceptualized by Chantal Mouffe and Ernesto Laclau. See: Mouffe and Laclau, Hegemony and Socialist Strategy (New York: Verso, 1985), xviii.

20 The festival is the fourth incarnation of an annual event organized by the city of Seoul, with its official name changing from “The Foreign Workers Festival” to “Migrant Workers Festival,” and to “Multicultural Festival” in 2007. This change reflects the shift in the government’s cultural policy towards migrant workers. And it also attests to the increasing rate of interracial marriage that is forcing both the central and municipal governments to make policy decisions on the country’s unanticipated multiculturalism.

21 For Harry Harootunian and Tomiko Yoda, the post-war economic prosperity and military security that Japan was promised by the U.S. came with the price of keeping the imperial dynasty intact and thus of delaying the very social reforms necessary for “[eliminating] prewar fascism and [putting] into place the foundations of a genuine social democratic structure.” In the immediate aftermath of the war, Japan, with American help, absolved the emperor of responsibility for the war, which began Japan’s endless deferral of acknowledging its war crimes. This long lasting post-war paradigm in Japan ended in the 1990s, with the recession that shattered the myth of Japan’s endless economic affluence. Harootunian and Yoda, introduction to the special issue “Millennial Japan: Rethinking the Nation in the Age of Recession,” of The South Atlantic Quarterly 99:4 (Fall 2000), 619-627.

22 As art historian Michael Sullivan recounts, The Rent Collection Courtyard epitomizes the Chinese government’s demand for sculptures as political propaganda. A group of anonymous sculptors collaborated to produce dozens of life-size sculptures in clay plaster to be housed in the courtyard of a former landlord in Sichuan. The contrast between feudal landlords and suffering peasants is rendered in the Soviet-style socialist realist depiction of human figures. Sullivan, The Arts of China, 5th ed. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008), 307-308. Cai Guo-Qiang is in fact the one who re-interprets this historical collection from a contemporary perspective by staging the process of sculpting The Rent Collection Courtyard in 1999 at the Venice Biennale’s Arsenale, and positing it as representation of the “failed promise of socialist China.” See Britta Erickson, “Cai Guo-Qiang Takes the Rent Collection Courtyard from Cultural Revolution Model Sculpture to Winner of the 48th Venice Biennale International Award,” in Chinese Art at the End of the Millennium, ed. John Clark (Hong Kong: New Art Media Limited, 2000), 184–89.

23 Discoplan was produced in collaboration with and exhibited in 2008 in the former Insa Art Space as part of a larger project, “Dongducheon: A Walk to Remember, A Walk to Envision,” which investigated the concepts of the border and neighborhood near the De-Militarized Zone. A small part of the exhibition was shown at the New Museum, New York in 2008 summer. http://www.newmuseum.org/exhibitions/398 (last accessed July 2010).